Eight Stories High

Long before Pearlie Harris M ’83 appeared on a mural high above downtown Greenville, she was a giant in education.

By Vince Moore

When Pearlie Harris M ’83 was told she would be part of a mural in downtown Greenville, South Carolina, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the desegregation of Greenville County Schools, she didn’t know what to expect. Lots of important people had helped with integration, and she assumed she would be one face among many.

The mural on Canvas Tower in downtown Greenville.

But what Harris would ultimately see was quite different. She was placed at the center of the mural, her 5-foot-3 figure covering the entire height of the eight-story building, her arms around a group of children representing the thousands of students she mentored during her teaching career.

Harris had checked on the progress of the mural as Guido van Helten, the celebrated artist from Australia, was working, and she had a good idea by the first visit that her appearance might be a bit more prominent. The artist was painting from the bottom to the top of the building, and Harris was able to recognize her blouse and the ring on her finger. What were the odds it could be anybody else?

“I was in my car and the first thing I noticed was my blouse,” Harris said. “I was shocked. All I could do was pull over to the side and cry. I called my son and told him, ‘I can’t believe it. They’ve put me on this mural – eight stories high.’”

Harris emphasized those last three words because, like anyone who has stood in front of the mural, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the sheer scale of what the artist did. And when people ask her what in the world she did to deserve such an honor, she laughs and says she has no idea. She can only say van Helten had read a series of articles in The Greenville News about the 50th anniversary of desegregation, which included a lengthy piece on Harris, and he was impressed by what he learned.

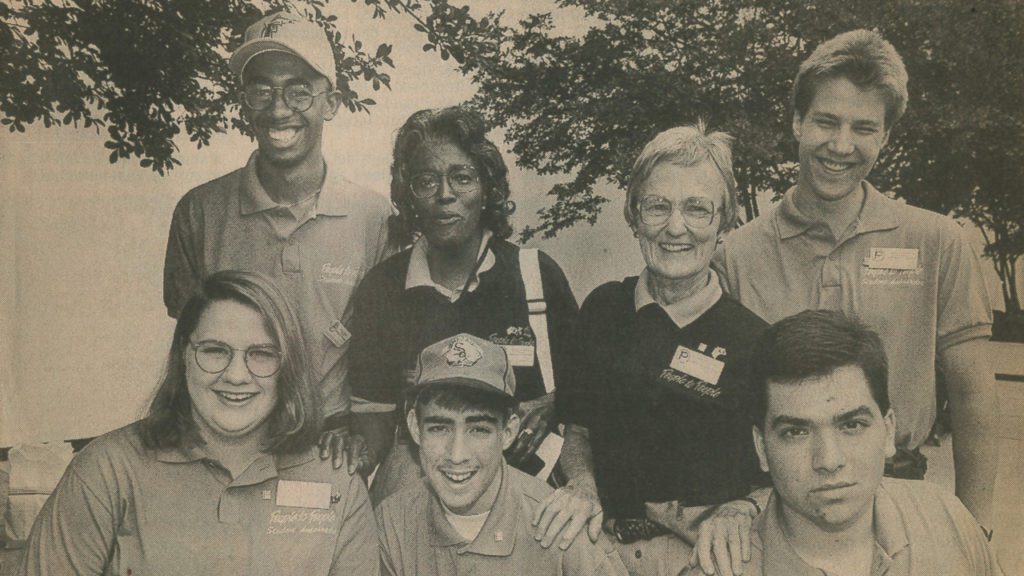

Harris (back row, second from left) in 1993, preparing to leave for a 24-day educational trip to Russia with a group of other educators and students from the Upstate region.

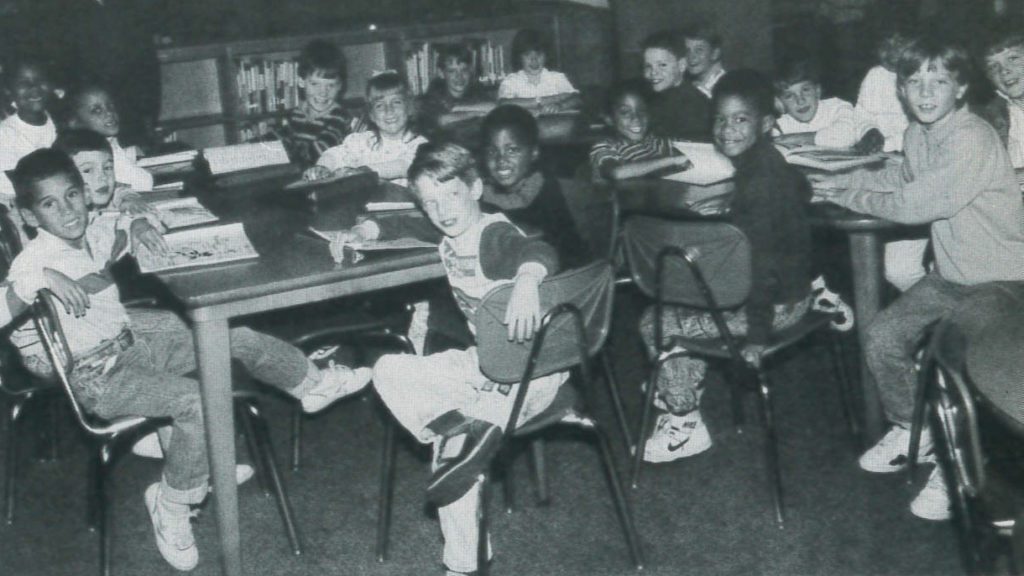

A newspaper article captures Harris assisting at a field day at Taylors Elementary School.

“I used to wonder, ‘How did this happen? How did we get to be the worst people in the world because our skin was black?’ And, to this day, I still don’t understand it.”

–PEARLIE HARRIS M ’83

Harris (seated) with other class officers in her high school yearbook, “The Tiger,” in 1952.

Harris teaches students in the Greenville County School District Challenge program in the 1980s.

“Guido came to my house and interviewed me, and he said he had read everything he could about me,” Harris said. “He said he thought I represented what he wanted to express. He also took a lot of photos of me, but I still didn’t know what to expect.”

If the artist was looking for a strong figure to put at the center of his work, he chose wisely. Even now, 25 years after her teaching career ended, the 84-year-old Harris exudes the same strength and confidence that allowed her to overcome the many barriers she faced over the years.

Harris grew up in the segregated South in Saluda, North Carolina, where she experienced racism in its purest form. As she and her three brothers walked to their all-Black school, they had to dodge rocks thrown by the children from the white school they had to pass. When she attended Barber-Scotia College, a historically black school in Concord, North Carolina, she watched the Ku Klux Klan burn a cross on the lawn outside her dormitory.

“When I was young, I would think, ‘I hope it’s not like this tomorrow,’” Harris says. “It was like a dream you were living in and it shouldn’t be happening. I used to wonder, ‘How did this happen? How did we get to be the worst people in the world because our skin was black?’ And, to this day, I still don’t understand it.”

But Harris felt safe and sure of who she was, largely because of her brothers and her father, a Baptist minister, who made sure his children knew the difference between right and wrong. When her father discovered that she and her brothers were secretly planning to retaliate by throwing their own rocks at the white students, he put a stop to it.

“He said, ‘No, you need to take a different route to school and avoid the trouble,’” Harris says. “’You won’t be like them. You’ll do the right thing.’”

Isolated, abandoned, underestimated

Work in progress on the portion depicting Sage Criss, 8-year-old daughter of Furman Assistant Professor of Health Sciences Shaniece Criss.

Sage Criss with Van Helten.

Harris began her teaching career in 1957 in the segregated elementary schools of coastal Beaufort, South Carolina, where she had as many as 40-50 students in her classroom and did her own research so she could update the textbooks that were often four-to-five years out of date.

She came to Greenville in 1962 and taught at two segregated schools, Washington Middle School and Burgess Elementary School. Then, in 1968, she was assigned to Crestone Elementary School, where she taught third grade and was the only Black teacher. All but one of Harris’ students were white.

She figures it was no accident she was the only teacher assigned to a portable classroom at Crestone, where she was isolated from the other teachers and forced to figure out things on her own. She went to a PTA meeting early in the year and heard the parents of her students express their concerns about the new Black teacher who couldn’t possibly know as much as the white teachers.

“I sat there and thought to myself, ‘This will be the best year your children have ever had,’” Harris says. “I made it my business to work 10 times harder and make my students accountable for what they were learning.”

And indeed, she did. By the end of the year, her students had fallen in line.

They stopped saying, “Hey, teacher,” or calling her by her first name, and they started referring to her as Mrs. Harris, as she demanded. The next year, the fourth-grade teacher who inherited her students knocked on the portable door with a question.

“Can you tell me what you didn’t teach them?” the teacher asked. “No matter what I talk about, they say they learned that last year.”

‘Because of her’

After Greenville County Schools fully integrated in 1970, Harris taught at Sara Collins Elementary and was one of the first teachers involved in the school district’s program for gifted students. She earned her master’s from Furman in 1983.

Greenville resident Barbara Reeves was in fifth grade when Harris was her teacher.

“The thing I remember most is that her classroom was such a positive and happy place,” says the 57-year-old Reeves, who has stayed in touch with Harris throughout the years. “She was always smiling, always making it fun to be at school. I ended up being a teacher myself because of her.”

Artist van Helten at work on the mural.

Harris retired from teaching in 1994, but she didn’t stop giving to the community. She has volunteered at numerous organizations over the years, including the Greenville Symphony, Centre Stage, Carolina Youth Symphony and Bon Secours St. Francis Health System. In 2009, she became the first Black person and first woman to serve as chair of the St. Francis Board of Directors. In 2011, The Pearlie Harris Center for Breast Health at St. Francis was named in her honor.

“She is an extraordinary person with a big heart,” says Greenville resident Camilla Hertwig, who has maintained a friendship with Harris since the days her son was a student in her classroom. “She is deserving of every honor that has come her way.”

Harris does plan to slow down at least a little bit now that she’s in her 80s, which means she’ll begin to limit her board activity and spend more time at home. She never remarried after her husband, Marine Master Sgt. James Harris, died in 1987, and she stays in close contact with her two sons, one of whom lives in Greenville.

Perhaps it’s fitting that the mural on the former BB&T building on College Street has Harris towering over an area of Greenville that was once the site of the Furman-run Greenville Woman’s College, which Harris couldn’t have attended because of her race. The fact that she has a place there now, eight stories high, surely says something about the progress the community has made.

“I hope people are inspired when they look at the mural, that they see love and compassion for other people,” Harris says. “I hope they see I was dedicated to my job as a teacher.”

“I hope people are inspired when they look at the mural, that they see love and compassion for other people.”

–PEARLIE HARRIS M ’83

Dr. Matt W. Wilson ’86 has made a planned gift of $4 million to Furman’s Institute for the Advancement of Community Health.