This article was written by Brandon Inabinet and originally published on February 26, 2018.

The current timelines of the university typically start with the founding date (1826) and then the story that the institution moved quite a bit from its founding until it found a home in Greenville (in 1852) and eventually northern Greenville county (1958). In a slightly more nuanced history, you might find that the antebellum moving had to do with financial exigencies, and the move out of downtown Greenville had to do with overcrowding. But of course, good historians always know there’s more to the story.

Before getting to the Winnsboro model, let’s start with an overview of the moves and the multiple motives for each location.

Edgefield

Religious revival with large numbers of new Baptist converts meant ambitious designs for the growing denomination in the Second Great Awakening. Basil Manly (eventual president and founder of the University of Alabama) helped recruit the Baptist Associations of South Carolina to fundraise, especially from the wealth of slaveholders, to build a schoolhouse for young boys in the backcountry who might go into the pastorate.

High Hills

Edgefield was too small a city to support an academic institution, but more importantly, too poor to recruit and pay for attendees. After the Georgia Baptists failed to deliver on cosponsoring the institution (instead launching their own institution), it was time to move. A home high above the marshes of malaria-infested Lowcountry South Carolina was the dream of most Charlestonians. That dream was synonymous with the “High Hills” of Santee. Many wealthy slaveowners had a summer home in High Hills, including the now-deceased school namesake, Richard Furman. The school moved near the land still tilled by Furman’s sons, including Samuel Furman, who would help ensure the institution remained solvent and operating, alongside its director, Rev. Jesse Hartwell. Directors and the Furman family members advocated for Baptists to pay for subscriptions for poor students to attend, while asking the SC Baptist Associations to fund campus and payroll.

Winnsboro

Jonathan Davis, major South Carolina politician, wealthy slaveholder, and leader of the SC Baptists, enticed these men to move the school to Winnsboro, and shifted leadership of the college to James C. Furman, another son of Richard and now son-in-law of Davis (James C. married Harriet Davis in 1833, and after her death in 1849, would marry her sister). With his wealthy plantation and the success of slavery around Winnsboro (symbolized in the gorgeous carriages that would bring slaveholders to the Fairfield Baptist Church), Davis purchased the land for the college near Fairfield Baptist Church and personally oversaw many aspects of construction.

The “failed” part of the Winnsboro plan was the labor experiment. When it opened in February 1837, the institute had 50 student boarders and 13 local students. Each student was required to work 2 half hours per day (for a total of an hour labor) in the fields surrounding the university–not much at all relative to the agricultural demands of the time. Teachers were expected to work alongside students, all under the supervision of a master farmer.

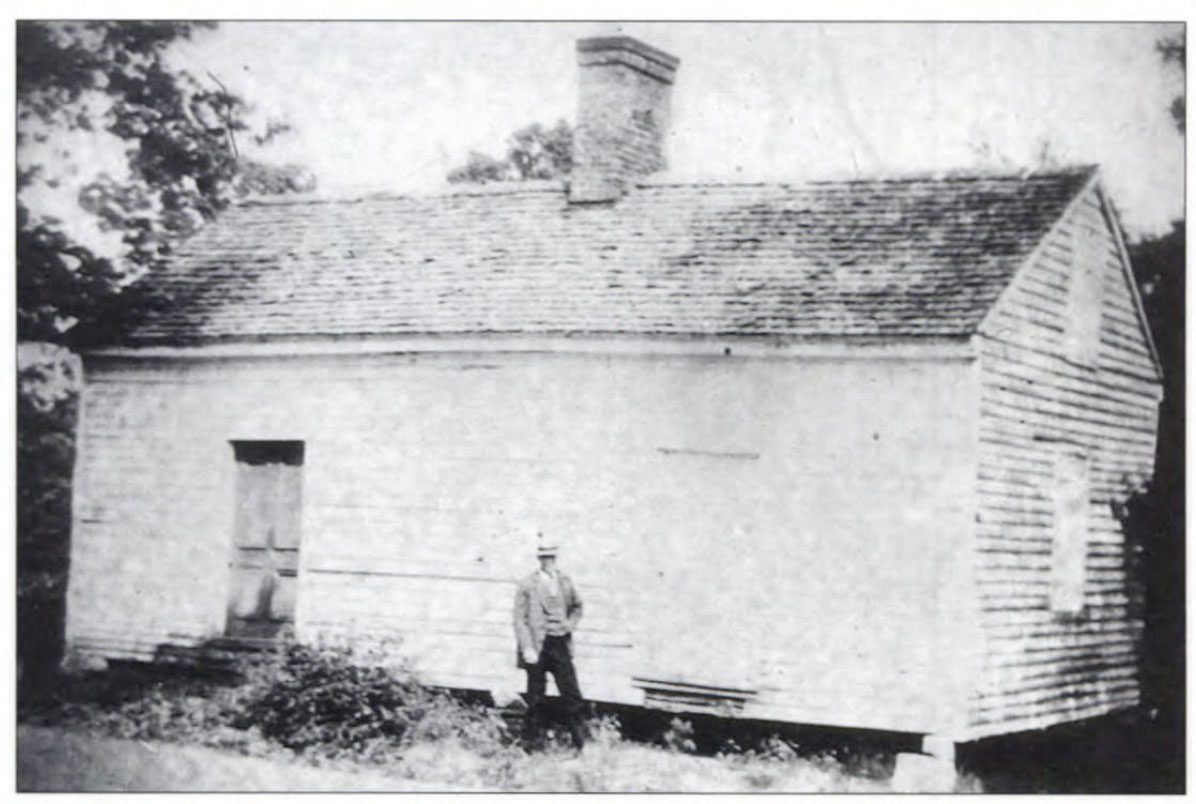

But rebellious students did not want to do the manual labor typically completed by African-American slaves and freed labor. Students instead frequented local liquor shops. The school burned to the ground in its first year (killing one student) and by the following year, a new model was created for students to live in one- and two-room cabins, placed in a semi-circle behind the rebuilt academic building. This arrangement helped to prevent the chaos of fire but made the unruly behavior of the boys even less easy to control and, as you might imagine, simulated slave quarters. Given the church associated with the college, where students were expected to attend, Fairfield Baptist, frequently had more black attendees than white, the feeling of slight was probably strong for these sons of privilege.

By 1841, there was already discussion of moving campus. The reasons were clear to later president William Joseph McGlothlin, a more “salubrious climate where there was a larger proportion of white people.”

The rest is the Greenville history that is more well known: a small building resembling slave quarters, now known as “Old College,” goes up on land donated by Vardry McBee, with classes starting for the newly branded “Furman University” on February 1, 1851. In a few years time, a beautiful campus is built according to the plans for an Old Main building by Charleston firm Lee and Hall, including the famous Bell Tower.

With each move, questions about the underlying economic conditions, race, and student conduct are often elided in the overview histories. It’s perhaps time that more material history gets its day in the sun.