This article was written by Brandon Inabinet and originally published on February 26, 2018.

Telling discomforting histories must also be tied with the stories of the persecuted who achieved measures of success within an unjust system. Andy Teye already has documented the laborers who helped build the downtown Greenville campus. And of course, we name this entire project for Abraham, the former slave of James C. Furman we hope to memorialize. The efforts of 2015 to commemorate Joseph Vaughn and all the students who desegregated various parts of Furman was a hallmark achievement.

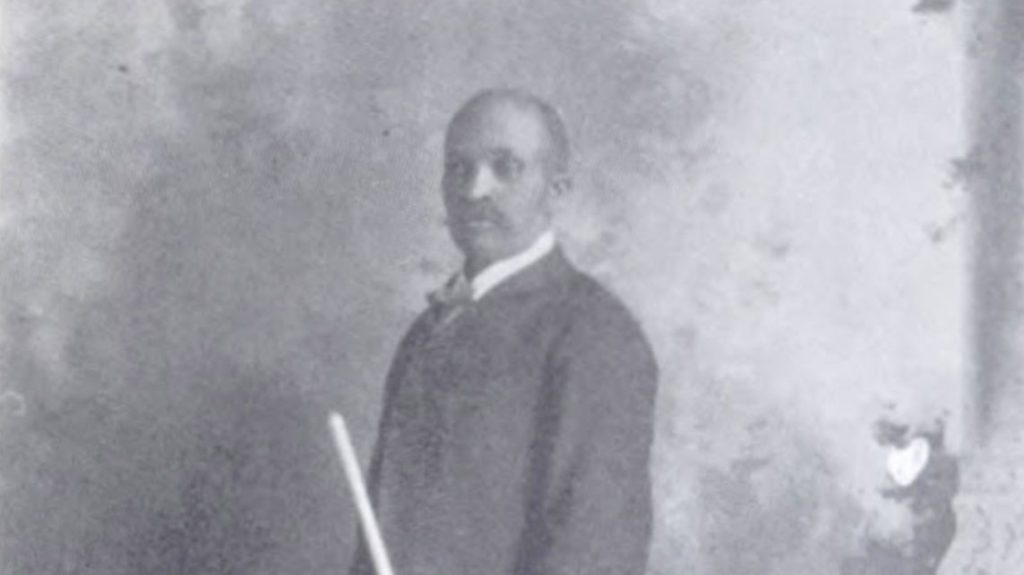

But perhaps the clearest example of a great figure in Furman’s early history is a man known to us only as “Murphy.” Caretaker of the Greenville Female College (which officially merged with Furman in 1938 but had been under shared leadership since James C. Furman’s time), Murphy was a trusted do-it-all man on campus. As one student memorialized in poetry,

“They are gone now–And Old Murphy has,

at last, laid down to rest

From his years of local service,

Giving G.F.C his best.

Who was Murphy?

Do you ask it? Just a plain old Negro man,

Janitor and humble servant.

Always loyal, always true,

Never asking much, but giving

Years of service, Gold and Blue.”

(from “Vision of the 80s,” by Gertrude Hoy Fripp)