This article was written by Andrew Teye and originally published on Aug 9, 2017.

As a student researcher in the Task Force, I was assigned the responsibility of investigating the construction of Furman’s early campuses. My research is therefore critical in the Slavery Project since it requires me to find leads on potential slave activity during the building of the University, and thus satisfy the initial inquiry of the Project.

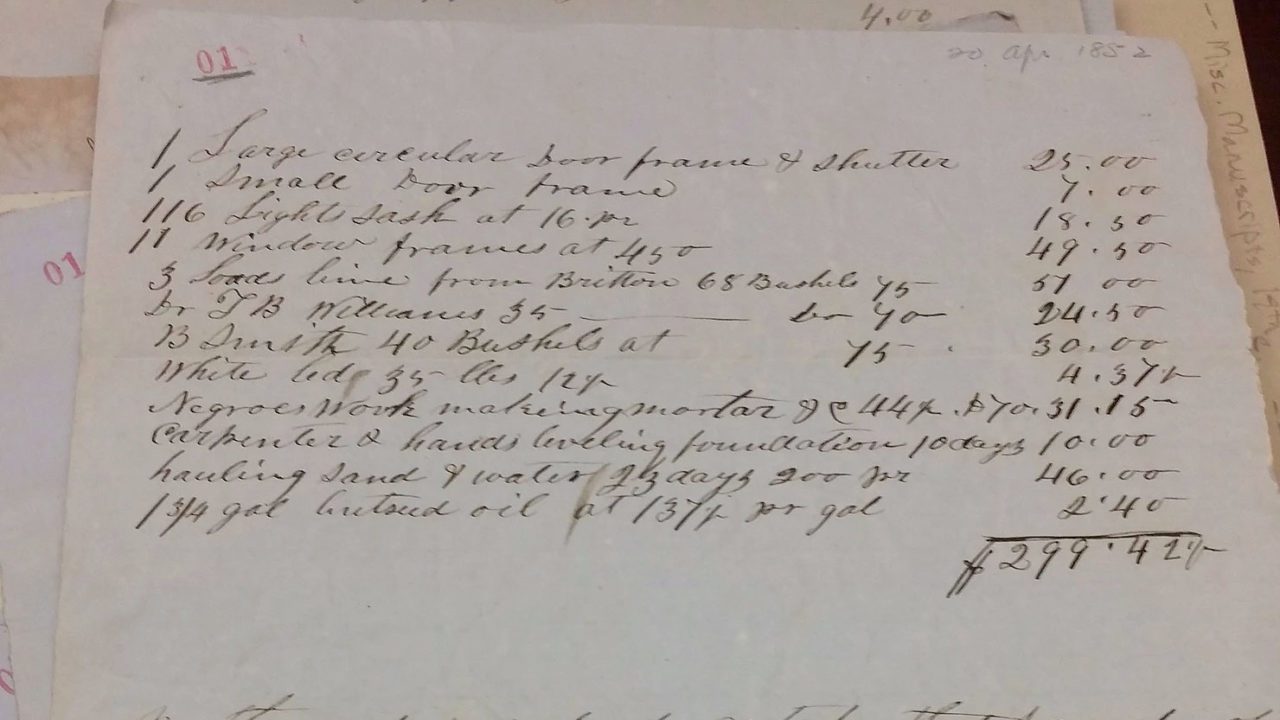

I first consulted Robert Norman Daniel’s book Furman University: A History (1951) to gain general knowledge on Furman’s early campuses and came upon an interesting statement. In his book Daniel mentions a report dated November 1st 1852 by Dr. H. W. Pasley, the head of the Building Committee at that time, in which Dr. Pasley recommended the hiring of slaves for the school’s construction at the beginning of 1853. His rationale for employing them was because he thought that “it was difficult to get white men to remain on their jobs long at a time” and he also believed that “in the long run Negro labor would prove cheaper“. However, Daniel made the claim that the tradition of using slave labor for construction during 1852 “is certainly not wholly correct” according to Pasley’s report.