This article was written by Brandon Inabinet and originally published on February 25, 2018.

Dr. Steve O’Neill has been hard at work over the past months to uncover the past, and one of the major histories he’ll be able to define in higher contrast is the role of Richard and, his son, James C. Furman. As a reminder, Richard is the namesake of the institution who died a year before its founding (named in memory by his friends in the SC Baptist Conventions) and James C. is the son who moved the institution to Greenville and led the school through Civil War and Reconstruction as its first President.

In this post, I’d just like to summarize the points of discussion and slow agreement reached among the researchers.

Let’s start with the similarities between the two men:

1. Both were considered very devout men and leaders in the Baptist church.

2. Both were widely imagined to be “benevolent” slaveholders (for all that’s worth).

3. Both were somewhat unusual for their time in becoming politically active at the highest levels.

4. Both lived through rapidly changing times, especially in regard to moral sensibilities.

5. Both were victim to and advocates for the conflation of religious theology with practices that supported their comfort, including racial slavery.

And then the contrasts:

1. While Richard had been nationally renowned in stoking revolutionary fervor in the South Carolina backcountry (Newberry area) against the British and as the creator of the Baptist church associations, James was known locally and regionally (in Winnsboro and then Greenville) for his leadership of the school and his fame came mostly through secession oratory.

2. While Richard was regarded primarily for his intellect, passion for freedom of conscience, and advocacy of education across races (as the vehicle for Baptist growth), James was regarded primarily for narrowing views about the role of races, women, and maintaining a southern order.

3. While Richard lived in a time when slavery was openly questioned nationally and presumed to be suspect to enlightened minds, James lived in a romanticizing period in which more extremist views were openly celebrated.

4. Thus, while Richard both helped and hurt the ideology of slaveholding in his public writings (by unsettling views of slave’s spiritual needs and education while protecting the Biblical defense of slavery), James worked to forcefully and unrepentantly solidify the “civil right” of slaveholding.

5. While Richard made his proslavery defense with some degree of humility and acknowledgment of varying legitimate views, James often employed divisive rhetoric to push South Carolina into antagonism and eventually war, while simultaneously undercutting the dignity of enslaved persons.

—————————–

For evidence of these claims, regarding Richard Furman, see the exposition letter, as well as the 1807 reply to the question “Should our Association take slavery and the treatment of slaves into consideration?” He wrote back: “Yes, in a wise, prudent, and becoming manner. Perhaps we can do something for the general good of the churches and the benefit of the slaves . . . but it is my opinion that undertaking anything of this kind under the idea of leading to emancipation or representing the holding of Slaves to be a Sin, would destroy the influence of the Association in the community at large.”

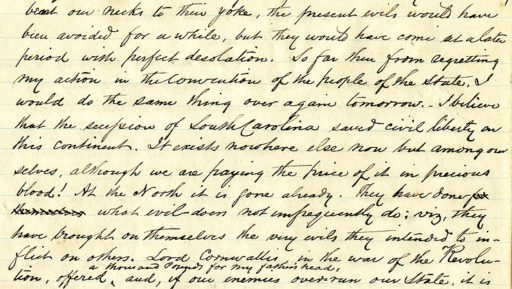

For James C. Furman, see the transcribed letter to the Citizens of the Greenville District (22 November 1860), as well as the letter to the Brushy Creek Baptist Church regarding their request that he not preach in his church, partly due to his zealous political advocacy (Oct. 18, 1863). His defense is as follows, essentially arguing that stooping to black rule would be the end of his liberties, an extension of the that wage labor in the North was no better than slave labor in the South:

“If we had meanly and cowardly bent our necks to their yoke, the present evils would have been avoided for a while, but they would have come at a later period with perfect desolation. So far from regretting my action in the convention of the people of the state, I would do the same thing over again tomorrow. I believe that the secession of South Carolina saved civil liberty on this continent. It exists nowhere else now but among ourselves, although we are paying the price of it in precious blood! At the North it is gone already.”