of the university

The Race to Reduce

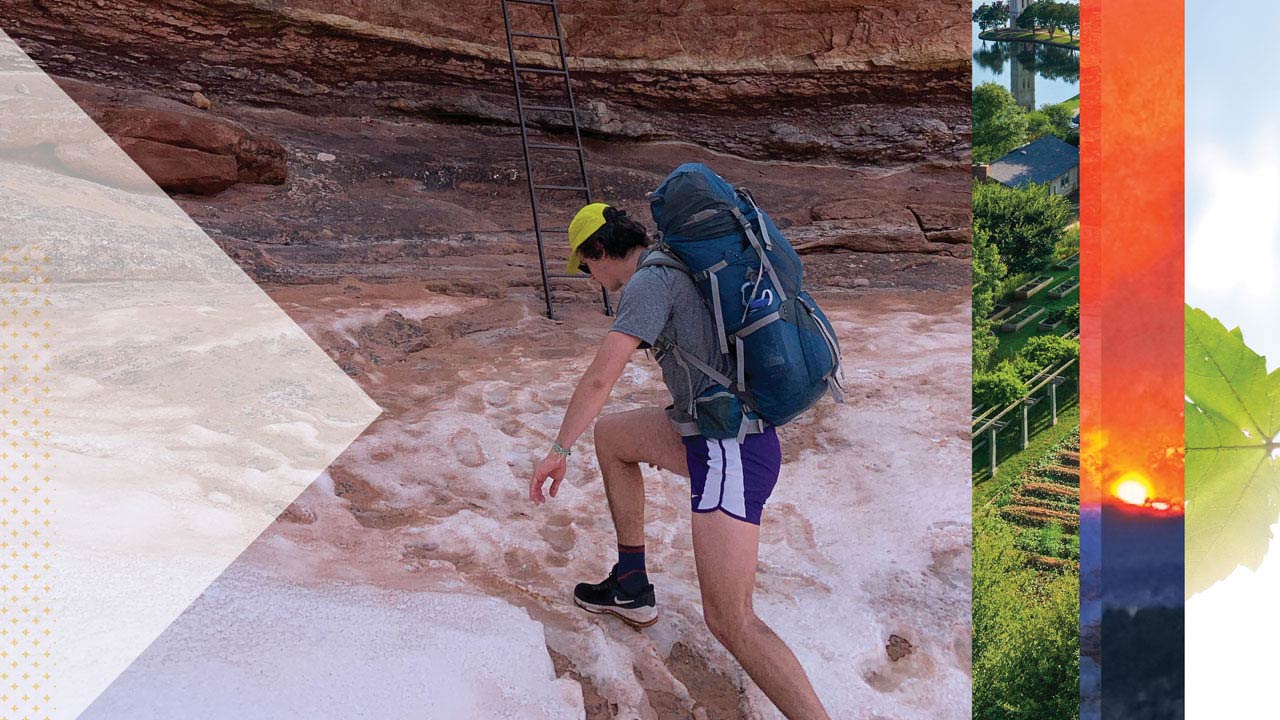

When Zane Newell ’24 was on a recent trip home to Salt Lake City, Utah, he looked out his plane window to gaze at the Great Salt Lake below. What he saw surprised him.

“Comparing it to what I saw last year, it was just different,” says the senior, who’s double majoring in sustainability science and Spanish. “Last year, we had one of our driest years on record, and now this year we’ve beaten all our records for the amount of snow. Just two very large extremes.”

But the unusual snowmelt Newell witnessed at 30,000 feet won’t make a longterm difference in the decades-long Western megadrought, caused by climate change and worsened by the rising demand for water. Newell remembers his fifth-grade field trip to the Great Salt Lake, when students floated in the salty water. Today, he worries that when he has children, they won’t experience nature the same way he did.

“I’m hoping they will. It’s something I want to share with them. It’s super important to me,” says Newell, a hiker, runner, camper and cyclist. “We’re going to be around, so let’s make sure there’s a planet that can support us.”

From left: Robert Engelhorn, president and CEO of BMW Manufacturing, Halsey Cook, president and CEO of Milliken & Co., and Furman President Elizabeth Davis, during the BMW Charity Pro-Am Sustainability in Business Summit. / Nathan Gray

How Furman approaches the climate crisis has a lot to do with what makes it distinct in higher education. Perhaps at its core is Furman’s commitment to justice and equity for all people. After all, climate change disproportionally harms those who contribute the least to greenhouse gas emissions and have the least resilience to its effects.

Preparing students for the world that greets them after graduation also is central to the university’s work. Graduates will be competing in a job market in which a growing number of roles respond to climate change.

Consider, too, the deepening collective conscience of young people today: The Princeton Review found that 67% of prospective college students say an institution’s commitment to the environment would affect their decision to apply to or attend it. And of that, 27% say it “strongly” or “very much” contributes to their decision.

“From a bottom-line perspective, students and parents, just like customers and investors, want to see educational institutions being sustainable and also teaching sustainability,” Furman President Elizabeth Davis said during the BMW Charity Pro- Am Sustainability in Business Summit, a gathering of industry leaders in June.

Furman is ranked third for sustainability among all baccalaureate institutions by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education, and it’s the only university in the South to make the organization’s Top 10 list.

“It’s an accountability measure for us,” said Davis, “to be sure we’re living up to what we’re actually teaching our students.”

SMALLER FEET

The Shi Institute for Sustainable Communities is updating the university’s 2009 climate action plan with the help of consulting services covered by a $20,000 grant from Second Nature, a nonprofit that advances climate action and resilience in higher education. The consultants are charged with identifying and modeling the costs of different strategies for reducing Furman’s greenhouse gas emissions.

And in May, the Furman Board of Trustees approved $3.5 million in energy efficiency upgrades. Among the improvements: Replacing 14,583 largely interior bulbs with LED bulbs (which also increases campus safety through better lighting), installing heating and cooling thermostat controls and sealing leaky HVAC ductwork to prevent 57,600 cubic feet per minute of air from leaking out of Furman’s buildings.

The project brings a variety of benefits, says Jeff Redderson, Furman’s associate vice president for facilities and campus services. “And certainly, on the most obvious level, we’re saving energy and reducing our operating expenses, which puts less pressure on increasing tuition,” he says.

WHEN WE PUSH THE LIMITS

In June, some 240 wildfires in Canada sent an alarming haze across the eastern United States, forcing people indoors and prompting the New York attorney general to alert consumers to possible price gouging on masks, air purifiers and filters.

“We’ve got to recognize there are ecological limits, and we’re pushing those boundaries,” Andrew Predmore, executive director of the Shi Institute for Sustainable Communities, told the BMW summit attendees.

FURMAN’S ENERGY EFFICIENCY PROJECT IS EXPECTED TO REDUCE CARBON DIOXIDE EMISSIONS EQUIVALENT TO:

- Removing 510 passenger vehicles from the road for a year

- Preserving 2,804 acres of forest (reaping the carbon sequestration benefits delivered by its trees)

- Charging 288,171,429 smartphones, or

- Powering 298 homes for one year

“All you have to do is read about those Canadian wildfires, and you will understand exactly what I’m talking about.”

To head off the worst effects of climate change and keep the planet livable – that is, to halt such extreme fires, floods, droughts, heat waves and species extinction – the global temperature cannot rise more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, per the Paris Agreement. That means that by 2030, we must cut greenhouse gas emissions by 43%, and by 2050 reach net zero – getting it to as close to zero as possible, with any remaining emissions offset or abated though carbon capture.

WHO GETS TO LIVE, AND HOW WELL?

In decades past, calls to save the spotted owl or “the whales” failed to move those who didn’t see individual species as part of something larger. Things have shifted in how we talk and think about the environment.

Andrew Predmore, executive director of The Shi Institute for Sustainable Communities, joins students at Chomarat North America, where students are helping to create an inventory of the company’s greenhouse gas emissions. / Owen Withycombe

“It’s really about human thriving, not just about conservation,” says Davis.

With that in mind, The Shi Institute is working with Geoffrey Habron, a sustainability sciences professor at Furman, and the Carolinas Collaborative on Climate, Health, and Equity, a collaboration with North Carolina State and other universities. The focus: to help low-income communities across the Carolinas, including historic Black communities in Greenville, adapt to climate change and soften its impact.

CLIMATE CHANGE IS ALREADY HARMING COMMUNITIES, AND ACCORDING TO THE SHI INSTITUTE:

- The effects of climate change are more severe in low-income communities.

- Increases in heat are linked to greater interpersonal violence.

- More frequent and severe flooding leads to more waterborne illness.

- Air pollution is tied to increased rates of asthma, COVID-19 deaths and dementia.

At the neighborhood level, the institute’s Community Conservation Corps, a partnership with Piedmont Natural Gas and Habitat for Humanity, has weatherized 181 local homes and offset 791 pounds of carbon dioxide.

On the business side, the institute partners with Sustain SC on the Sustainability Leadership Initiative, which trains working professionals on climate change and other topics. Graduates make up a network of sustainability professionals across the state.

Several larger companies in South Carolina have ambitious climate goals and are pressing their small suppliers to follow suit, a charge that can be challenging for smaller businesses. So, students with The Shi Institute worked with two local industrial clients over the summer, Chomarat and Mosaic Color and Additives, taking the first step to reducing emissions: creating an inventory of each manufacturer’s greenhouse gas emissions.

A manufacturer in Greenville, South Carolina, may seem far removed from the rapidly shrinking Great Salt Lake. But it is directly tied to our future – the immediate survival of some and the long-term quality of life for others.

“What we’re really talking about is the critical work of meeting human needs within the boundaries of what our natural ecosystems can provide over the long haul,” Predmore told summit attendees.

“This is a health, justice and security issue, now and into the future.”