A Southern University Embraces a Sacred Japanese Tradition

by Scott Carlson

Originally published in The Chronicle of Higher Education on August 15, 2008.

In its final days of reconstruction, the Place of Peace is a hallowed gallery of sounds. If you close your eyes and listen, you can hear each one registering on the wind and rustling trees on Furman University’s campus. The krish-krish of footsteps over the broken and leaf-littered ground. The skrit-skrit of trowels, pushing plaster onto walls and into corners. The ping-klunk of a board falling into place with a hammer blow. And, occasionally, the banshee scream — rheeeee! — of a circular saw or belt sander, forcing wood to comply where hand tools won’t do.

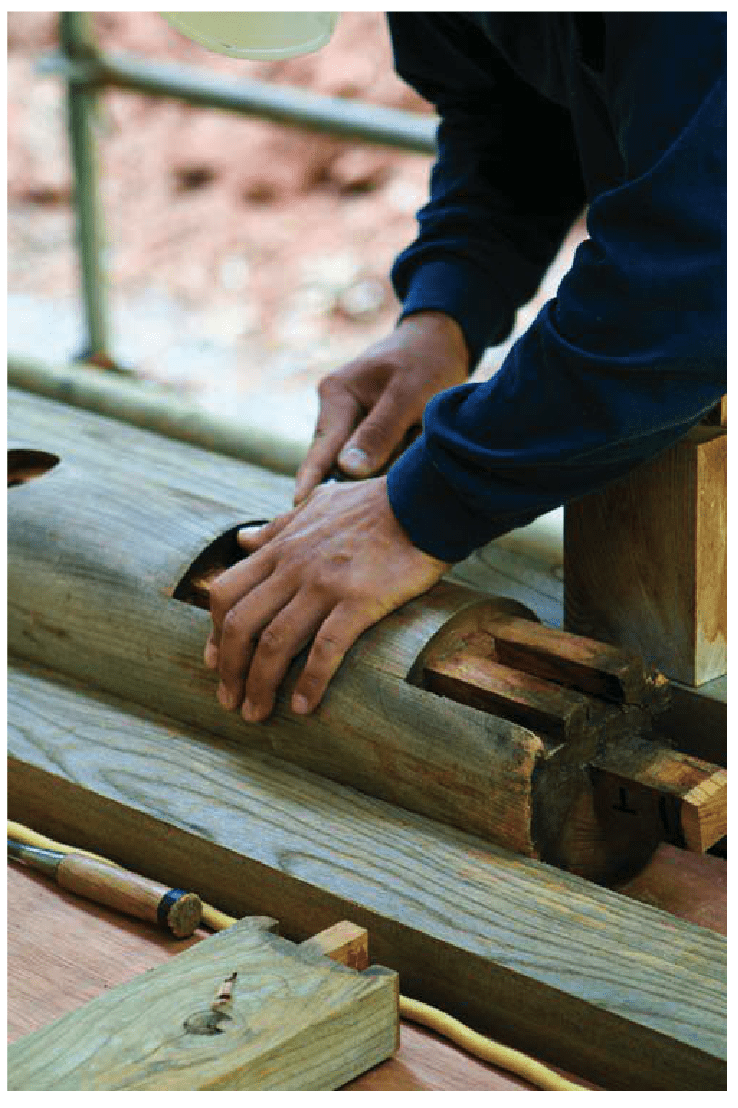

The men here — all of them Japanese, all journeymen in the ancient art of building Buddhist temples — do not speak, even, for the most part, with each other. The task at hand is exacting, serious, and sacred.

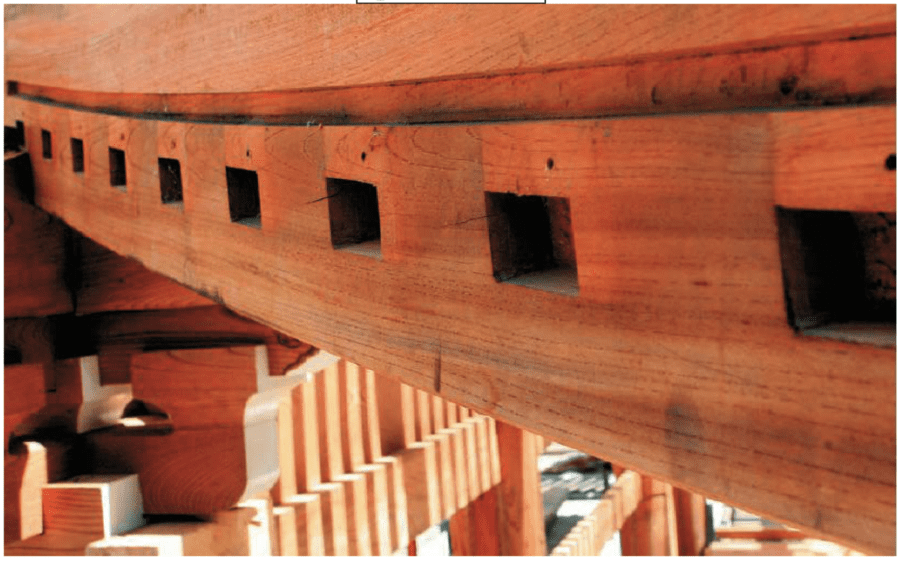

This reconstitution of a Buddhist temple — which was disassembled into 2,400 pieces in Japan, shipped in four containers across the Pacific Ocean and through the Panama Canal, and reassembled in South Carolina — is a unique undertaking, especially unexpected for a Southern college once closely associated with the Baptist church.

But then, how Furman decided to take on the project in the first place is an unusual tale. The temple once belonged to the Tsuzuki family, which owned and operated a textile company in the Carolinas and built the Nippon Center, a Japanese cultural center in the middle of Greenville. The American textile industry has been on a downward slide for decades, and a few years ago, the Tsuzukis needed to sell off some of their properties both here and in Japan. The Nippon Center would have to go, and Furman, which is trying to build a top Asian-studies department, approached the family about taking some artifacts from the center.

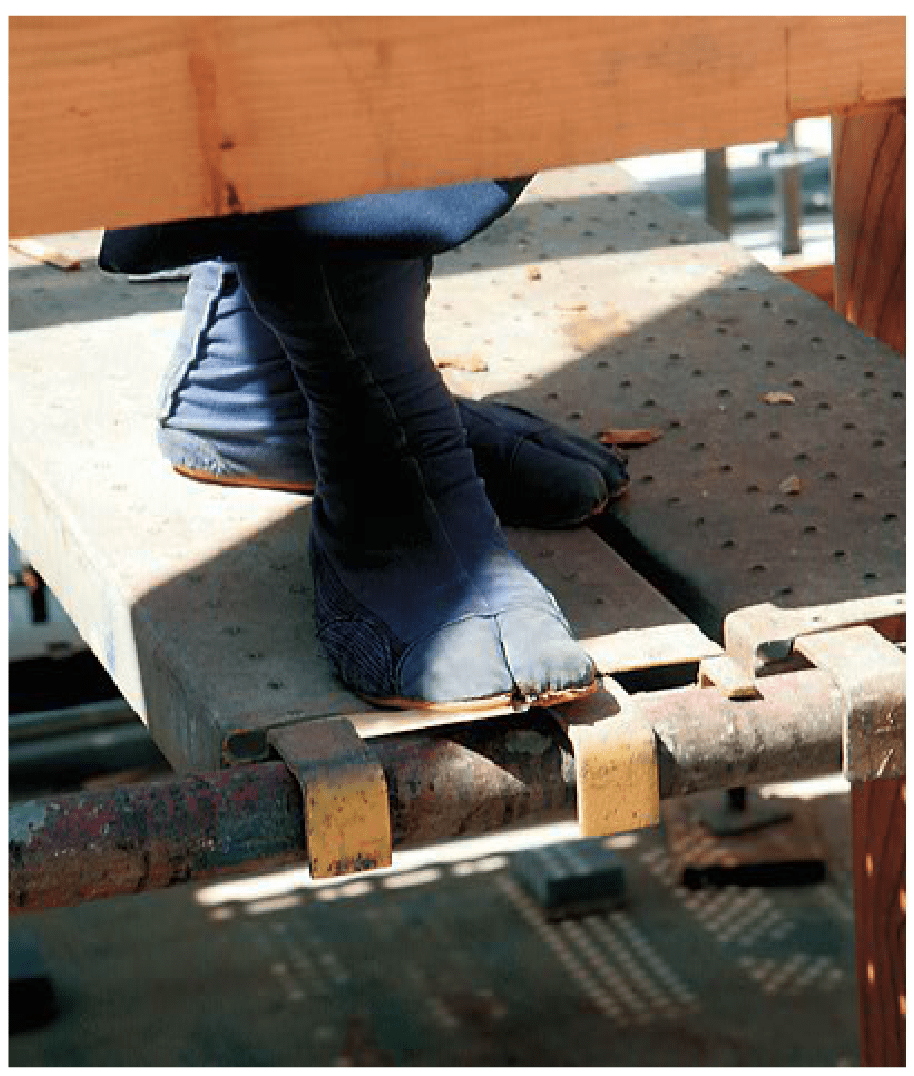

An artisan wearing traditional footwear with rubber soles to improve balance and tractions stands in “migi hamni,” or” right posture,” as he works on the temple.

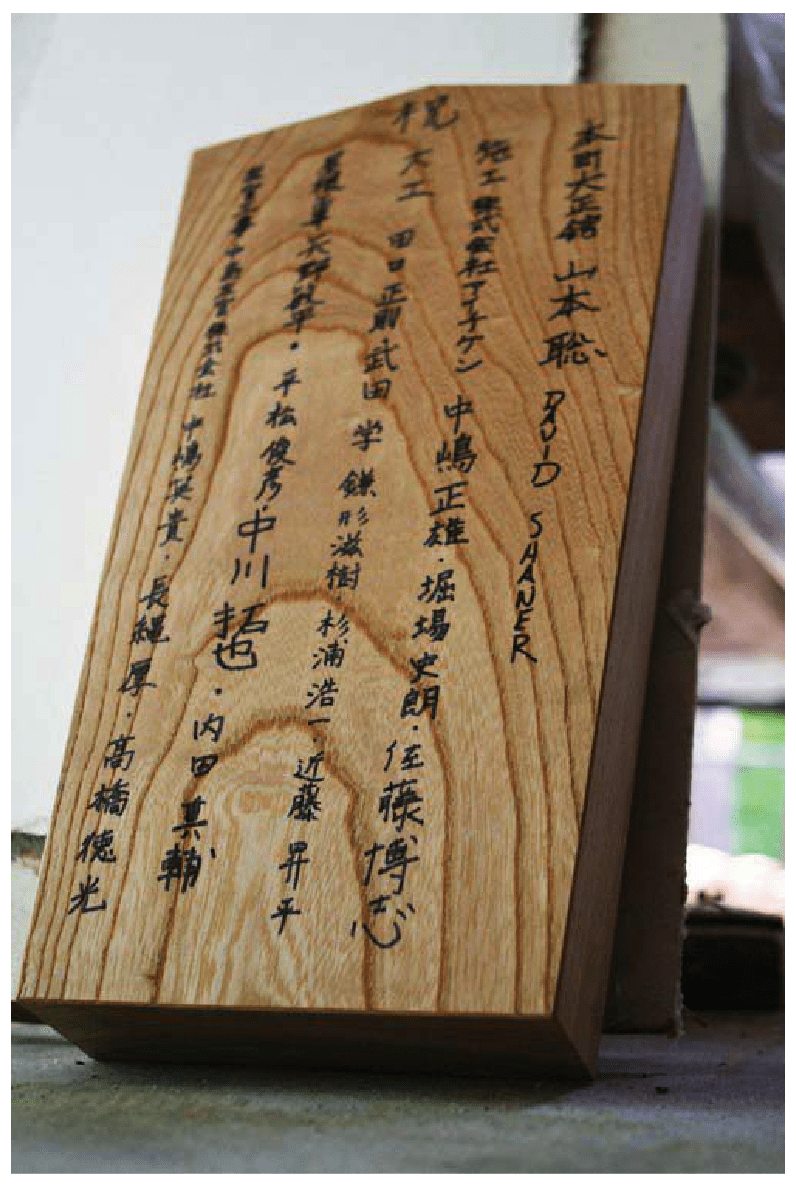

The Tsuzukis also owned a plot of land in Japan upon which sat the family’s handcrafted temple, built by some of the best artisans in Japan from the finest materials. The land’s buyers had no use for a temple and said they would have to tear it down if it were not moved by January 2006. “We essentially said to the Tsuzuki family that we would love to relocate this temple here,” says David E. Shi, Furman’s president.

The matriarch of the family, Chigusa Tsuzuki, had long ties to Furman. Twenty-six years ago, she began taking courses in Japanese philosophy with David Shaner, a professor of philosophy and Asian studies here. Shaner is one of the world’s leading aikido instructors, and later she became one of his aikido students — and a friend.

When she died in 1995, a cherry tree was planted in her honor in an Asian garden near where the temple is being reconstructed. Asked what the temple project means to him, Shaner, standing on scaffolding surrounding it, is visibly moved.

“I feel blessed,” he says. “To be at the epicenter of this, because of my connection to the family, I

just can’t believe it. I just look at this every day, I feel like I am in Japan.”

Furman has tended to have a more politically and socially conservative climate than other liberal arts colleges. “Thank God for David [Shi] for shepherding this project, where we could have had a very conservative alumnus or a nonvisionary president who said ‘A temple on campus? Oh, no — that’s dangerous turf.'”

The Place of Peace cannot technically be called a temple anymore — the butsudan, or shrine, once encased at the center of the temple, has been removed and is in the family’s possession.

The Place of Peace cannot technically be called a temple anymore — the butsudan, or shrine, once encased at the center of the temple, has been removed and is in the family’s possession.