of the university

Furman Engaged Invites Us to Be Curious

Have you ever wanted to try Peruvian chupe de camarones, find out where Danes get their joy and learn about the bacterial load in leafy greens – all in one day?

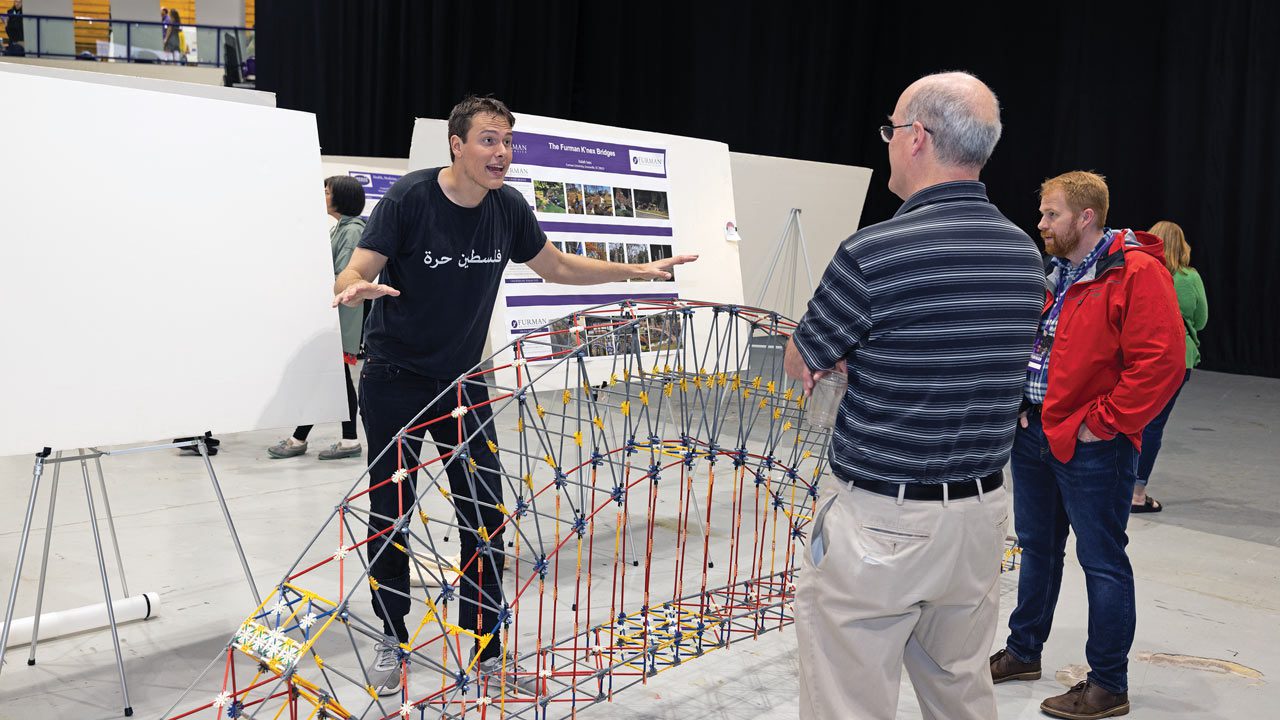

If so, it’s not too soon to think about attending next year’s Furman Engaged, as these were just a few of the activities the 15th annual celebration offered attendees this past April.

During this Furman tradition, students publicly share their research, internships, study away and other scholarly and performance activities. This year’s Furman Engaged was part of the launch weekend for Clearly Furman, the Campaign for Our Third Century. Here are some of the topics students presented, showing their peers, faculty, staff and the community what’s possible at Furman:

HOW CLERGY MEMBERS TALK ABOUT RACISM

Sabrina Strickland-Harris ’24 and Virginia Wayt ’23 studied what members of the clergy told their congregations after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 and the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

They transcribed, coded and analyzed dozens of recorded sermons from around the time of those events. Their preliminary findings: Many of those sermons tended to frame controversial issues as individual spiritual problems, not systemic social ills.

“Clergy have regular opportunities to share messages about race and racism to an audience,” said Wayt. “They are engaging with current issues, but they’re doing so really vaguely.”

A CARD FOR THOSE OFF MOMENTS

Greeting cards to commemorate birthdays, anniversaries and other major life events are easy to find. But what can you send a friend who has lost their phone, or is struggling to adjust to a new haircut – or just plain having a bad day? Rebecca Cowles ’23 might have you covered. The studio art major created “The Small Things,” a line of watercolor greeting cards you won’t find at Hallmark.

6,000 TICKS

For some of us, ticks are a nuisance while hiking. For African farmers, tickborne diseases that strike livestock can be devastating to a family’s livelihood. In Africa, 37% of the land mass is made up of farms, which produce 70% of the continent’s food supply.

Kaya Frawley ’24 traveled to a game reserve in the Limpopo province of South Africa to learn how habitat and climate affect tick abundance and diversity. While on the reserve, Frawley dragged a pole draped with cloth across three different types of habitat to collect and identify ticks: 6,000 of them in all. “Tick-borne diseases can have a local, national, continental effect,” she said, adding that they decrease livestock reproduction and milk production and raise mortality rates. Eco-tourism and game ranching are also affected. Meanwhile, ticks have grown resistant to the acaricides pesticide.

Her recommendation is to go back and closely examine the multitude of ecological relationships involving ticks to develop better tick-control methods.

THE CYCLICAL NATURE OF TRAUMA

Caitlyn Horton, a student in the Master of Science in Community Engaged Medicine program, examined the existing research about the greater likelihood that women experiencing trauma – such as physical assault, intimate partner violence and childhood abuse – later experience homelessness later in life. These women have a greater risk of isolation, psychiatric disorders and hormonal imbalances, among

other symptoms, she explained.

She recommends trauma-informed care and communication among professionals who support women experiencing homelessness and examining sources of trauma to better design responsive resources, among other measures.

“Having child care resources, addiction treatment, domestic counseling – these are all things that will better serve this population,” she said.

HOW’S THE WEATHER?

Computer science majors Ian Cho ’24 and Luke Kvamme ’23 wanted to know how reliable weather professionals are and how their prognostications compare to those of amateurs.

“Having accurate weather forecasts is something that everyone can relate to,” Kvamme said. Using Python, the two compiled and analyzed data and forecasts from 11 sources across 61 major cities in the U.S. and Canada, collected twice a day for five years. That’s more than 400,000 HTML files equaling about 125 GB of text data.

When comparing forecasts to actual recorded temperatures, Cho and Kvamme found that while TV meteorologists are pretty accurate, weather-savvy amateurs aren’t bad. The amateurs were only off by about 2.5 degrees in their forecasts compared to the professionals.