Charting clarity: Furman researchers see 18th Century maps through different lenses

Say you’re planning a trip across South Carolina because you’re in the market for real estate. You set out on your horse, because it’s the 18th century, with a map that details rivers and hills and open fields for farming. But when you get into the country you see the fields are forested, and the riverbanks are settled by Indigenous tribes.

Map makers 300 years ago weren’t incompetent, they were commercial, according to a team of researchers at Furman University who represent a variety of perspectives, including biology, ecology, cultural anthropology, sustainability science, classical studies and ancient mapping. Their work was published in the journal Landscape Ecology.

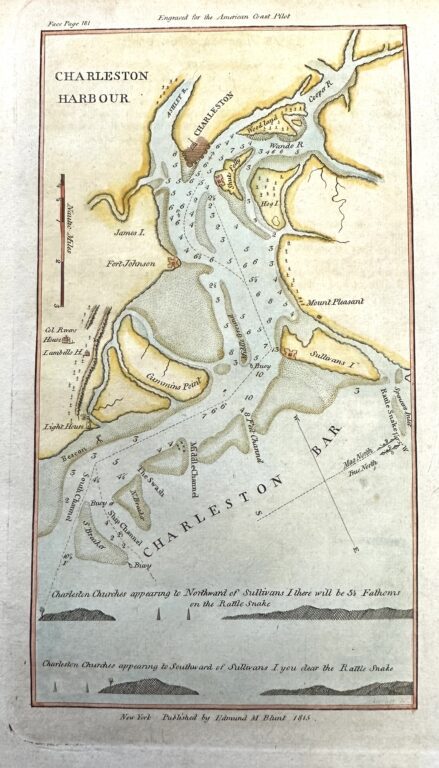

An 18th Century map of Charleston Harbor, from Furman’s library’s Department of Special Collections and Archives.

A lot has changed in mapmaking, but that one principle still holds true. Open Google Maps for directions to someone’s house and you’re bombarded with labels for Waffle House, Home Depot and Starbucks.

The lesson, especially for ecologists and other scientists, is to “consider who was behind the information and what motivated them. Maps are not a neutral representation of data,” said John Quinn, an associate professor of biology, director of environmental studies and senior author of the study.

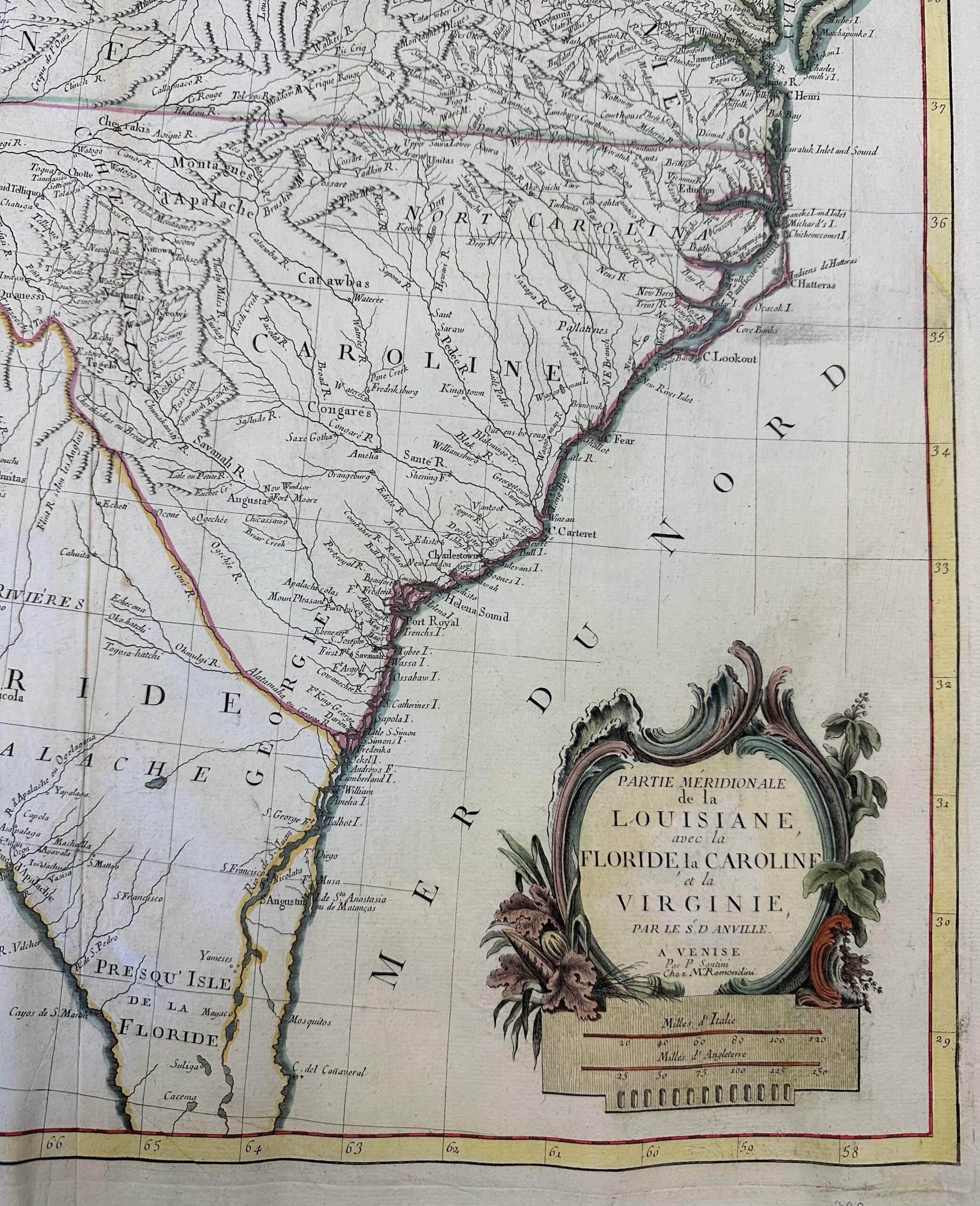

Quinn began the project by studying maps of South Carolina from the 1700s housed in Furman’s Duke Library Department of Special Collections and Archives. He saw them through a landscape ecology lens, wanting to know if they could help inform conservation goals today. He asked two Furman colleagues to join him on a research project: Chiara Palladino, an assistant professor of classics who specializes in interpreting how space is represented in ancient documents, and Karen Allen, an associate professor of sustainability science and anthropology, who was using human records to understand past landscapes and land uses.

Quinn was interested in learning about forests in South Carolina’s Upstate area. He was surprised that the maps didn’t depict many forests, while rivers were abundant and very well marked.

Palladino and Allen knew, through their respective lenses, that forests weren’t included on the maps because they were less valuable than arable land, and rivers were an important channel for commerce.

“Maps are not objective representations of reality,” Palladino said. “We look at the landscape that surrounds us and we project values onto it as we travel through it with different perspectives. What are the underlying principles?” In that sense, maps can reveal more about the people who created them than the land being charted.

Three maps of the same geographical area and same time period might each have different information, Palladino said, based on the map makers’ interests, values and priorities. Most often, the privileged or dominant interests prevailed. Maps of the new United States were often meant to sell land to Europeans, which is why Indigenous peoples’ settlements were often left off.

One map that interested Palladino was George Hunter’s map of the Cherokee Country from 1730. The map is a travel log, with notes about stops along his route. “We found specific notations about the potential of the land,” and how it was good land for growing grain, Palladino said. But it wasn’t. The map “was not an objective representation of the land.”

Emma Grace Homoky ’22 also worked on the project as a student during her junior year. When she moved on to a different project, Kylie Gambrill ’23 picked it up the summer before her junior year and worked on it through her senior year. Gambrill, who double majored in anthropology and environmental science, expanded the project, ordering more maps of South Carolina, but tightening the focus to the 1700s, when Indigenous people were quickly being displaced and choosing maps that noted Indigenous settlements and land use. In the end, the group looked at 14 maps from 1711-1773.

“Exploring the Indigenous displacement and acknowledging the colonial past of the land is difficult, but it’s really worthwhile in acknowledging people,” said Gambrill, who is a Furman Fellow.

An undercurrent in the scientists’ paper is the interdisciplinary approach to their work. They each brought a perspective to the maps that enriched the overall interpretations and added value to the project.

Funding for the project was provided by the Furman Humanities Center, The Shi Institute for Sustainable Communities and the Associated Colleges of the South.