of the university

As He Tells It

The life of journalist Peter Gwin ’88 is one of pirates and fixers and brushes with everyday humanity.

The stories were his portal, his magic carpet, a trap door that opened to reveal the whole world. So, it’s not hard to understand how writing similar stories became his dream, the motivation for so many choices he would make: A road trip with friends was a chance to send dispatches back to his prove he could make it in another country. And since the magazine that he hoped would one day hire him was based in Washington, D.C., that’s where Peter Gwin would be based, too.

“The dream was always to go to National Geographic,” says Gwin, who’s been under the spell of the iconic jonquil-yellow frame since his grandfather gave him a subscription as a kid.

The magic is sustained by the human urge to know. “It’s a basic human impulse – we want to see what’s out there,” he says. “I’ve always had an insatiable appetite for it.”

The dream became reality in 2003. Today, Gwin is an editor at large for National Geographic and co-host of the award-winning “Overheard” podcast.

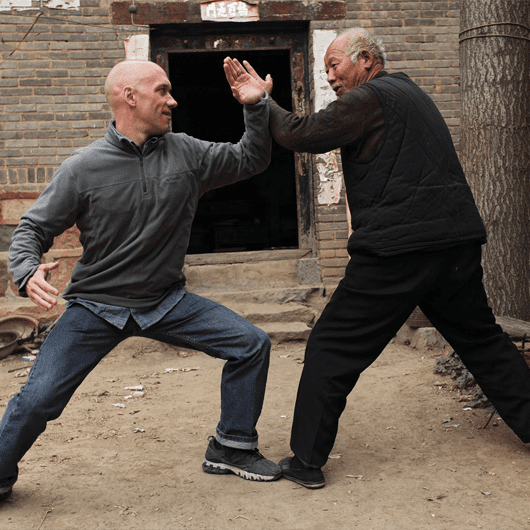

In 2010, while searching for kung fu masters in the Song Mountains of Hennan province, Gwin encounters Fan Fuzhong, who traces his kung fu lineage to Shaolin Temple monks. / Fritz Hoffmann

DISPATCHES

His favorite class his first year at Furman was first-year composition. He wanted no part of Shakespeare but knew he’d never get an English degree without the bard. English professor John Crabtree, who died in 2019 at age 93, “turned out to be one of the best teachers I’ve ever had,” Gwin says.

Crabtree brought the old words to life in a way that “you could see what everyone was raving about,” he says. The class was foundational to his “appreciation for the language, a way to think about text.”

Gwin wrote for The Paladin and was editor of The Echo, a student poetry journal that he helped expand into a full literary magazine.

After graduation, Gwin and four friends piled into a Nissan Pathfinder pulling a borrowed pop-up camper and hit 36 states in two months before the military and careers and graduate school took them separate ways.

Gwin sent accounts of the trip to This Week in Peachtree City, his hometown newspaper, writing about breaking down in Wyoming and meeting a group of road-tripping young women at the Statue of Liberty.

His parents would get stopped at the grocery store by shoppers wondering where the guys were going next.

“That really fired me up,” Gwin says. He taught English in Botswana for Harvard’s World Teach program then hitchhiked across Africa and wrote another series of dispatches, this time faxing them confidently to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

But he returned to Georgia to learn not one had been published. The editor told him the stories sounded more like magazine journalism.

It’s hard to imagine criticism that would have been sweeter to his ears. Gwin considers that period excellent practice. He learned how to begin conversations, to ask questions, to manage logistics in a foreign country.

He learned how little he knew.

“If you travel, you realize pretty quickly that places are very often far different than you imagined,” he says.

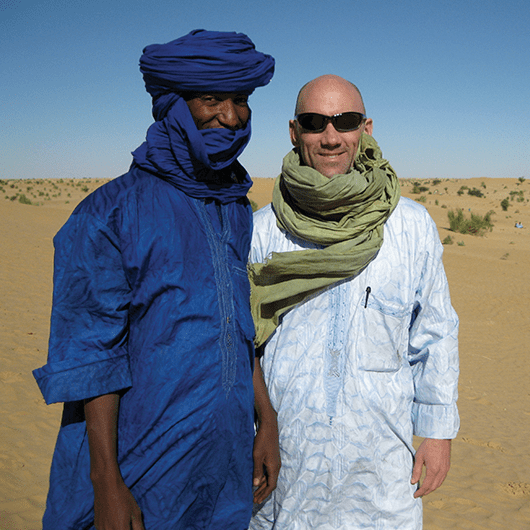

Gwin in Timbuktu / National Geographic

REJECTION

Gwin moved to D.C. and was waiting tables when he got wind of a job writing scripts for educational film strips for National Geographic.

“I don’t care,” he decided. “It’s a writing job, inside Geographic. I will work my way from the film strip department to inside the yellow border.”

He sent a résumé, but his dad said that would never be enough: Go down there, look them in the eye, shake hands, he advised.

A friend who worked in the photo department got him into the building but the person responsible for hiring was unpleasantly surprised to find Gwin in her office. As he made his pitch, she picked up her phone and reported an intruder on the floor.

“At first, I was like, ‘Holy crap! There’s an intruder?’ I had no idea she meant me,” Gwin says.

When the truth hit him, he left at a run and escaped to a nearby bar, sweating like a fugitive. It would be almost a decade before he entered the building again.

Instead, he took a job with Europe Magazine.

For nine years he covered topics such as the transition from the Common Market to the European Union, learning as he wrote how to help readers understand a complicated world. But he never stopped watching the job postings from National Geographic. And the second time he applied, no one called security.

Gwin relaxes in the Alaska Western Arctic. / National Geographic

PEOPLE

Please don’t ask his favorite story. It’s an impossible question for someone who has written about pirates in the Malacca Straits, traditional Chinese medicine, and rhinoceros poaching.

“What really stays with me are the people that you experience the reporting with,” Gwin says, recalling a game ranger in South Africa and a fixer in China, where he was reporting on aging kung fu master.

A fixer is almost always the unsung hero of a story, “the person who gets you into this world that you’re completely unfamiliar with and in many ways unprepared for,” he says.

Gwin stayed multiple times with the family of his fixer in Timbuktu. When Gwin was writing about sensitive subjects, including terrorism and black-market smuggling, the man’s 12-year-old nephew often led him safely through the labyrinth of the city at night.

“Many sources didn’t want to be seen talking to a foreigner, so I’d visit after dark wearing a turban covering my face like a lot of the population in Timbuktu,” he says.

These kinds of experiences are as important to the stories as the interviews.

“I come back with this richer sense of being part of humanity,” he says.

PODCAST

At the office, every conversation, from elevator chitchat to a formal meeting, is liable to turn into a fabulous story.

“Never get into a storytelling contest with photographers,” Gwin says. “Never do it.” He was on assignment with one photographer friend who told him about covering Yasser Arafat’s funeral. The crowd had surged and pushed Gwin’s friend into the Palestinian leader’s grave.

Stories like that don’t typically end up in the magazine, but they’re a regular part of Geographic life. Gwin recognized their parallel power to connect with listeners eager to understand the world.

“Overheard,” which began in 2019, deepens listeners’ connection to both the publication and the world of exploration. Gwin and his co-host Amy Briggs open the door on conversations such as “how to investigate an ancient pharaoh’s murder or how to set up a camera trap for a Himalayan snow leopard.”

It’s the exact kind of portal that drew him in all those years ago. “The thing that makes human beings different from other species is the thing that drives us to see what’s the next hill over,” Gwin says.

“Geographic is really just tapping into that thing that’s inside all of us – to go see.”