Cox, seated third from the left, with Furman’s American Chemical Society in the 1964 Bonhomie.

An Indispensable Brilliance

The contributions of Brad Cox ’65 affect the daily lives of billions of people who rely on Apple products.

By Clinton Colmenares

Many of us have to look no further than the palms of our hands to realize the impact Brad Cox ’65 made on the world.

Brad Cox ’65 during a television interview.

In the early 1980s, Cox, who grew up on a dairy farm in Lake City, South Carolina, shut himself in his home office with a passel of computer equipment and emerged two weeks later with the programming language Objective-C. Cox’s company sold the language to Steve Jobs, who was running a company called NeXT during a moment of banishment from Apple. When Jobs went back to Apple, he took Objective-C with him. It became the basis for the Mac operating system and the root stock for Swift, the language used today in all Apple devices.

Cox died from complications of Parkinson’s on January 2 at his home in Manassas, Virginia. He was 76.

At Furman, he encountered his first computer, “a hand-cranked calculator in the chemistry department,” he says in a Computer History Museum video. Cox majored in chemistry and math, then, intrigued by how the brain works, earned a Ph.D. at the University of Chicago in mathematical biology and finally a post-doctoral fellowship at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.

“Brad got all the brains in the family,” says Dan Cox, Brad’s brother. He thinks of his brother when he pulls up a spreadsheet on his phone.

Etta Glenn met Cox when he was playing in a bluegrass band at a festival. “I had a little Yorkie, and Brad walked up and said, in his Southern accent, ‘Sure is a cute little puppy you have there.’ That was all it took.” The couple married in 1976.

What made Cox special, Glenn says, was his 175 IQ. He also played guitar and piano, traveled extensively with her, and loved being outdoors.

Stock imagery of a coding language.

Objective-C was one of the first widely accepted object-oriented languages, says Bryan Catron, an instructor in computer science at Furman who taught the language in an app development MayX class. Swift, the language used to program iPhones, and Java, another popular programming language, are both rooted in Objective-C.

It offered a “much more conceptual view of the world,” Catron says. Pre-object-oriented languages were more fundamental. “If we were building a structure, with C you’d be talking about bricks. With an object-oriented language, we’re talking about rooms and hallways and stairs.”

With Objective-C, “you see the world as it is,” Catron says. That was a new ability that led to desktop interfaces that allow users to manipulate computer files as they would real files.

Glenn says the advancement “set the world on its ear.”

Cox was invited to give talks about his development all over the world, and Glenn accompanied him.

Cox’s business partner and mentor, Tom Love, presented Objective-C to Steve Jobs. Jobs had been ousted from Apple and had created a new computer, NeXT. Jobs used Objective-C in NeXT and took the technology with him when he went back to Apple.

The ubiquity of iPhones and Macs throughout the world might suggest a proportionate share of riches to Cox for his early development. In fact, Glenn says Jobs offered to license Objective-C to NeXT for $5 per future unit sold. But the members of the board of Cox’s company demanded a cash price that would prove relatively small.

Glenn says Cox “never recovered” from that deal. Still, Cox realized his work was something special. In a 2011 interview with MacTech magazine, Cox was asked: “So Apple’s sold something like 30 million iPods and iPhones? How does it feel to have Objective-C running in the palm of so many people’s hands?” Cox laughed. “Yeah, it’s pretty nice,” he says.

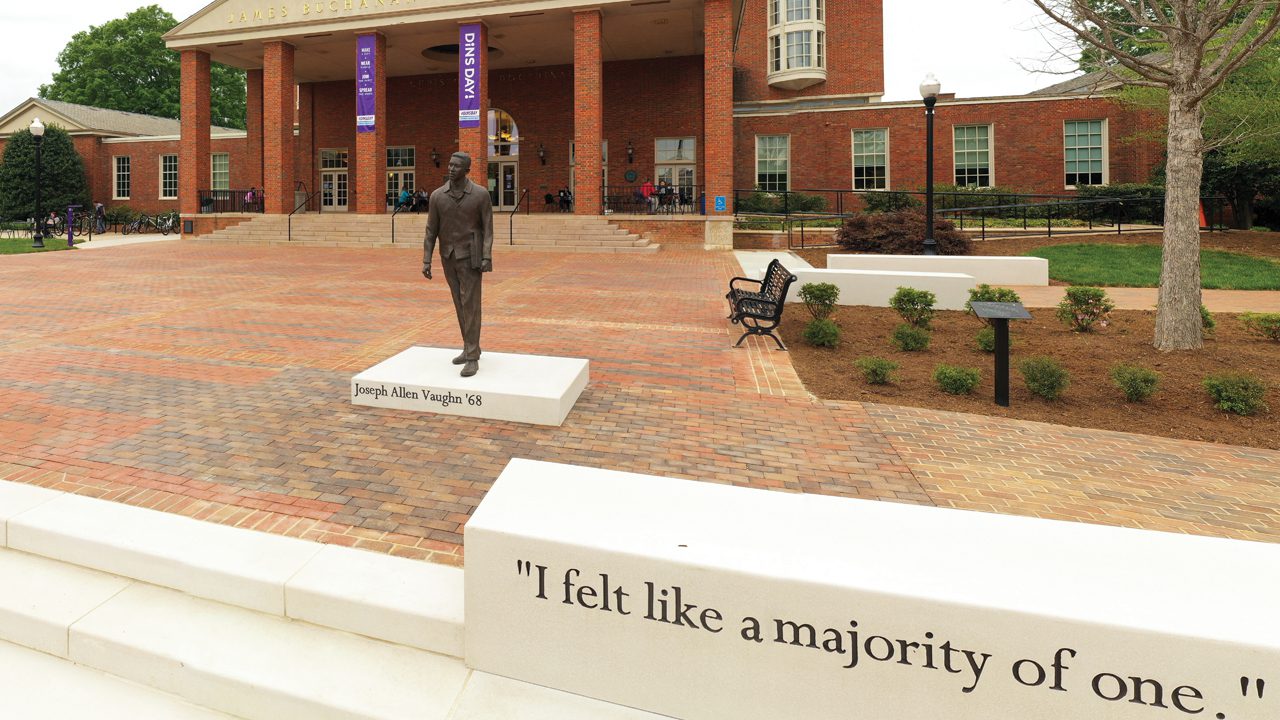

On April 16, we celebrated the historic unveiling of the Joseph Vaughn ’68 statue in honor of his profound legacy.

James A. Lanier Jr. ’79 and Mary Anne Anderson Lanier ’79 make a new $1 million commitment to Furman.