The Pragmatic Sensei

by Candace O’Connor

Originally published in Furman magazine on April 1, 2009.

With worldly sounds in the distance — cars rushing past, doorbells ringing — more than a dozen students of Buddhism gather each Monday evening to meditate quietly and ponder eternal questions, such as the purpose of life.

The setting for this practice session is not a temple but the back room of First Unitarian Church in St. Louis, Mo. And these men and women are a distinctly non-traditional group.

Although some are formal trainees in black robes, others are lay members in blue jeans. Some are self-described Jews or Methodists, while others are simply seeking greater awareness. No one has a shaved head; one young man, in fact, sports shaggy blond dreadlocks.

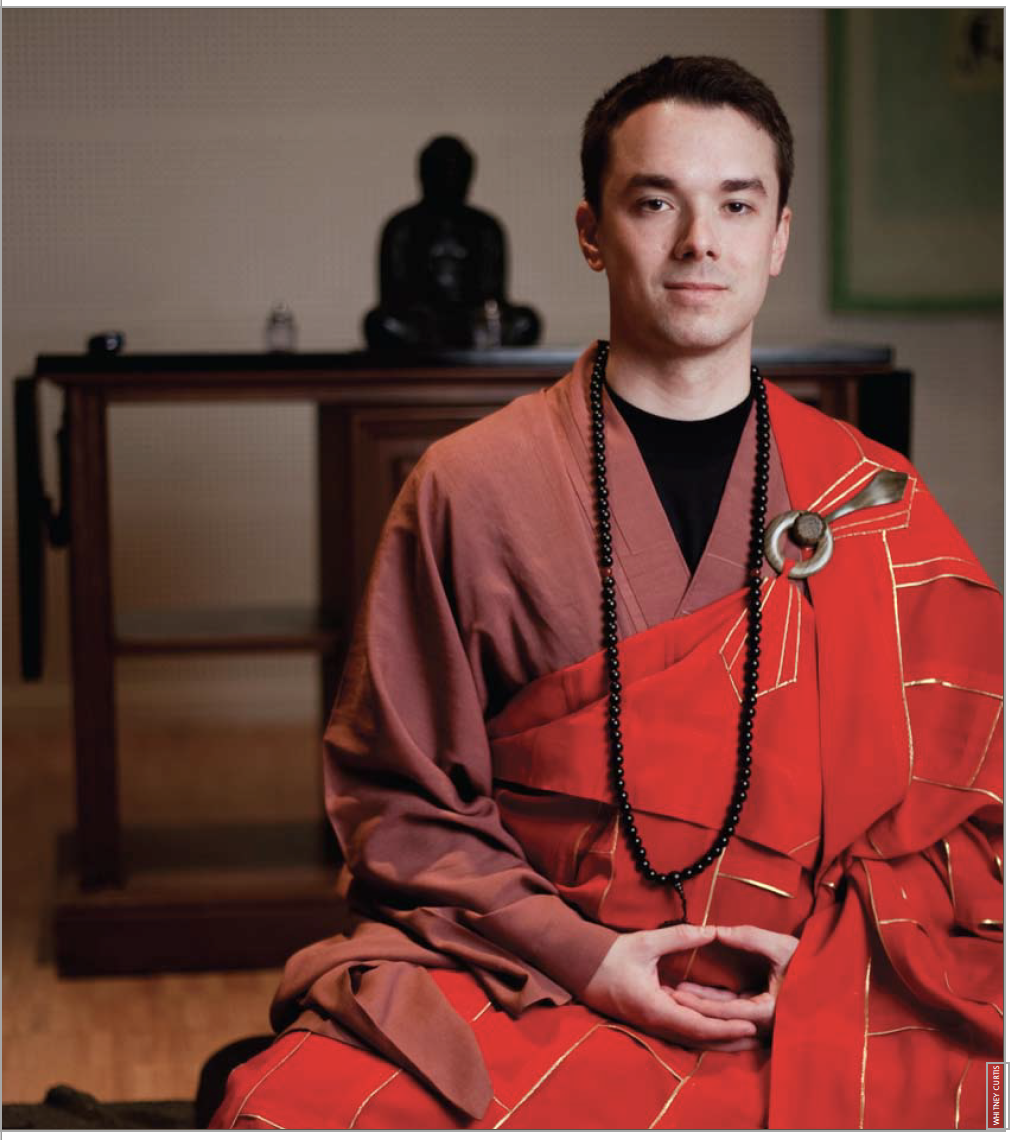

Jim Eubanks

Most unexpected of all is their teacher, or sensei, sitting cross-legged in the middle of the floor. He is a small, earnest, 25-year-old man, younger than most of his pupils.

Yet he is dressed in the purple gown and red robe of a Buddhist master, and he is already an abbot — currently the youngest abbot, or spiritual leader, of any Buddhist order in the world.

In this room he is Shi Yong Xiang sensei. But he is better known to Furman classmates and faculty as Jim Eubanks ’05.

“What is deeply true is that Jim is an old soul,” says David Shaner, Gordon Poteat Professor of Philosophy and Asian Studies, who taught Eubanks at Furman and serves today as his sensei. “He is incredibly mature for his young age. While he is extremely genteel, kind and compassionate, he has a very powerful will underneath all that. He is wise well beyond his chronology.”

Despite his youth, Eubanks has managed a remarkable feat. After the sudden death of his first Buddhist teacher in October 2006, Eubanks — the senior student — was named the Dharma heir, which meant that he became head of his St. Louis-based order, responsible for its growth and nurturing.

That task is complicated by its groundbreaking nature. Through its monastic body, the Order of Pragmatic Buddhists (OPB), and its lay body, the Center for Pragmatic Buddhism (CPB), Eubanks’ group is helping to define a new, accessible, culturally relevant strain of Buddhism — nudging its boundaries in a more liberal direction.

“Earlier this year, the term ‘pragmatic Buddhism’ was finally adopted into the normal lexicon of American Buddhism, and we are the only group that actually uses that term in our name,” Eubanks says, adding: “It is easier to be black or white, category A or category B. My experiences, at least, have been very much shades of gray.”

Eubanks himself lives the busy, complex American life that he wants the CPB to reflect in its teaching. As its leader, he has heavy responsibility for his 10 formal students, four of whom are already novice monks and full members of the OPB. They embark upon a rigorous training program that lasts at least six months; their climb through the monastic ranks takes them from novice to cleric and then master.

At this early stage in their training, Eubanks speaks to them individually each week for half an hour, monitors a discussion they host in an online forum, and holds a monthly group reading session. He sends out a regular newsletter, and at the Monday meetings, he delivers a “Dharma talk,” always followed by a lively question-and-answer session.

“In much of Buddhism, the teacher’s Dharma talk expounds on the canonized text,” says Eubanks. “When I give the talk, it may come from The Atlantic, The Wilson Quarterly or something else highly Western. Then we have group discussion, not often done in Buddhism. Our members love that and consider it integral to their practice.”

But mingled with his Buddhist world, he has another life, as a student at Logan College of Chiropractic. He is scheduled to graduate this spring, with a master’s degree in sports medicine due in August.

Eubanks, who completed his chiropractic studies, credits his parents, Jim and Malinda, for their steadfast encouragement and support of this interests.

Like Buddhism, chiropractic medicine divides into its own camps — a majority favoring a musculoskeletal focus and a vocal minority with a metaphysical bent. Eubanks is squarely on the medical side, helping patients with joint manipulation, rehabilitation and muscle training.

“Chiropractic medicine is another good way to teach people self-empowerment,” he says. “For example, we can give someone who doesn’t exercise a concise introduction to it. Something they can do twice a week for 10 to 15 minutes under initial monitoring. Something that fits in their weekly schedule and really works.”

While some forms of Buddhism demand a monastic life and celibacy, Pragmatic Buddhism does not. Eubanks’ teacher was married, and he has a fiancée, Komal Patel ’06, an intensive-care nurse at Missouri Baptist Hospital. They met in anatomy class at Furman and plan to marry next spring.

“If we live an isolated life, without family or job — and we just have to worry about cultivating flowers — it is relatively easy not to have stress enter into your mind,” says Eubanks. “The hard thing is dealing with such stresses as paying taxes, worrying about whom to vote for, raising children. Yet those things are at least as valuable, and not enough emphasis has been placed on them.”

Eubanks grew up in an All-American household with his sister Laura, who just completed her sophomore year at Furman. His father relocated frequently in his job with Bank of America, and Eubanks, born in Danville, Va., was uprooted many times as a child, living mainly in eastern North Carolina and Baltimore.

“In retrospect,” he says, “that was a good experience because it taught me some lessons of Buddhism: impermanence and change. It allowed me to appreciate that perspective.”

His family attended liberal Lutheran churches, and Eubanks, always interested in religion, considered becoming a minister. In high school he played lacrosse and studied Gong Fu, a physically strenuous Chinese form of martial arts. Holding postures for a long time introduced him to meditation, which improved his focus and made him curious to learn more.

Then trouble struck. One February day his senior year, he thought he was catching a cold. But soon he felt excruciating pain in his abdomen and back. The diagnosis was Crohn’s disease, a chronic bowel disorder, and he underwent surgery. As he recovered, unable to eat, he began mulling over life-and-death issues: Why are we here? Is there a reason for suffering?

“It was also challenging for me to imagine how suffering like mine could happen — on a much broader scale and in more profound ways — to people who had many fewer resources than I did,” he says. “I began to move away from the explanation that it happened for a reason toward the idea that it just happened, and we have to learn to deal with it.”

When it was time to look for a college, one of his father’s colleagues (Gene Godbold ’77) suggested Furman, and on a visit Eubanks fell in love with the school. The campus was gorgeous, he says, and he liked the close faculty-student relationships and the strength of the pre-med program.

During his freshman and sophomore years he spent time in religious organizations, often discussing Christianity outside of class. He also took courses that gave him new insights. They included David Rutledge’s “Bible as Literature” class that considered the Bible from a historical perspective; Bryan Bibb’s course on wisdom literature of the Hebrew Bible and Apocrypha; and Gil Einstein’s psychology course that illuminated how the mind and memory work.

“The Bible is filled with historical reflections, written by human beings,” Eubanks says. “God evolves over time and so does Satan; the Satan in Job is not the same Satan as in the Gospels. That evolving perspective is important to understanding that humans are evolving, too.”

Gradually, Eubanks began moving away from an anthropomorphic image of God. Is he theistic now? “I don’t have any conflicts with it,” he says, a bit enigmatically.

Most of all, he began to reconceive his view of Jesus, shifting away from the notion of Christ as sacrifice, paying for human sins.

Jim Eubanks assisted his sensei, professor David Shaner, during Furman’s dedication of the Place of Peace, a former Buddhist temple.

Now, he says, he focuses on the way Jesus lived: his compassion for the weak, his selflessness.

Eubanks says he doesn’t know whether there is life after death, but it is not something that concerns him. “I don’t know anyone who can report on the afterlife, but I do know what is going on in this world,” he says. “Over my 78 years or whatever my life expectancy is, my energy has to be devoted to something that is fruitful here. My time is best spent dealing with the pressures and stresses and hardships of life today.”

By the end of his sophomore year, Eubanks was reconsidering a medical career and thinking instead of attending graduate school in comparative philosophy. Then, at the start of his junior year, and again six months later, he had emergency surgery for painful intestinal adhesions, caused by his earlier operation. It was another blow, he says, and helped swing him back toward the medical field.

The same year, he took what was for him a seminal course: Mark Stone’s philosophy class in American pragmatism, which highlighted for him the importance of focusing on clear-cut problems, including the need to alleviate suffering.

Stone referred Eubanks to Shaner, chair of the philosophy department and senior faculty member in Asian Studies. On leave at the time, Shaner invited Eubanks to his home, and they discussed Shaner’s experiences in Japan and in the Ki-Aikido community, where he is chief instructor of the Eastern Ki Federation. Shaner also practices Buddhism and has for 40 years studied the teachings of Master Koichi Tohei, who is now 90 years old.

Eubanks began taking courses from Shaner and others in Asian Studies and decided to seek a Buddhist teacher who could lead him in further study. Through an Internet search, he happened upon the Venerable Ryugen Fisher of St. Louis, and they started corresponding. They met and Eubanks decided to pursue formal training, which turned into weekly sessions after he moved to St. Louis in 2005.

He was drawn to the order, in part, by its philosophical heritage and focus. In Buddhism, teaching lineage is important, and Fisher had been a student of Holmes Welch, a noted Harvard-based scholar of Chinese Buddhism and Taoism. Over time, Fisher — whose order was called the Dragon Flower Chan Temple — had worked to develop a pragmatic new form of traditional Chan Buddhism, coining the term American Chan Buddhism.

After Fisher’s death and his appointment as abbot, Eubanks began moving the order still further toward pragmatism. He met some resistance from traditional communities that opposed his interpretation, but he persisted, renaming his group the American Chan Buddhist Center and later the Center for Pragmatic Buddhism. Today the CPB belongs to the 14-member St. Louis Buddhist Council, and all but one group is cordial to him, he says.

He also formed an eight-member advisory board composed of leading figures in the field. Two are Furman faculty: Shaner and religion/Asian Studies professor Sam Britt. “They help by giving me resources and double-checking ideas, but having this group also shows our seriousness,” he says. “Transparency is important to us, and if we are opening ourselves up to this caliber of people, it is hard for anything to be hidden.”

At this Monday session Eubanks is explaining the roots of Pragmatic Buddhism, and his group is peppering him with questions. As he answers them, carefully and quietly, the group inclines respectfully to listen. “How did he learn this so early?” they murmur to each other during a break.

Shaner has an explanation. “I think we all have a calling. It just takes some people longer than others to figure out what their calling is, but Jim gravitated toward philosophy and practice at an early age. It could be that this is part of a connection that has been with him through many lifetimes.”

Mounted on the wall in this Unitarian space is a picture of William Greenleaf Eliot, a 19th-century minister who espoused what he called “Practical Christianity.” On the floor behind Eubanks is a small altar adorned with candles and the figure of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha. Together, these images seem to embody where Eubanks has come from and where he is heading.

“Buddha questioned why there is suffering. He went through intense suffering himself and developed what we now call Buddhism. This statue is a symbol of the human ideal that we aspire to,” says Eubanks, adding pragmatically: “What matters are our actions and the ability to do what he did.”