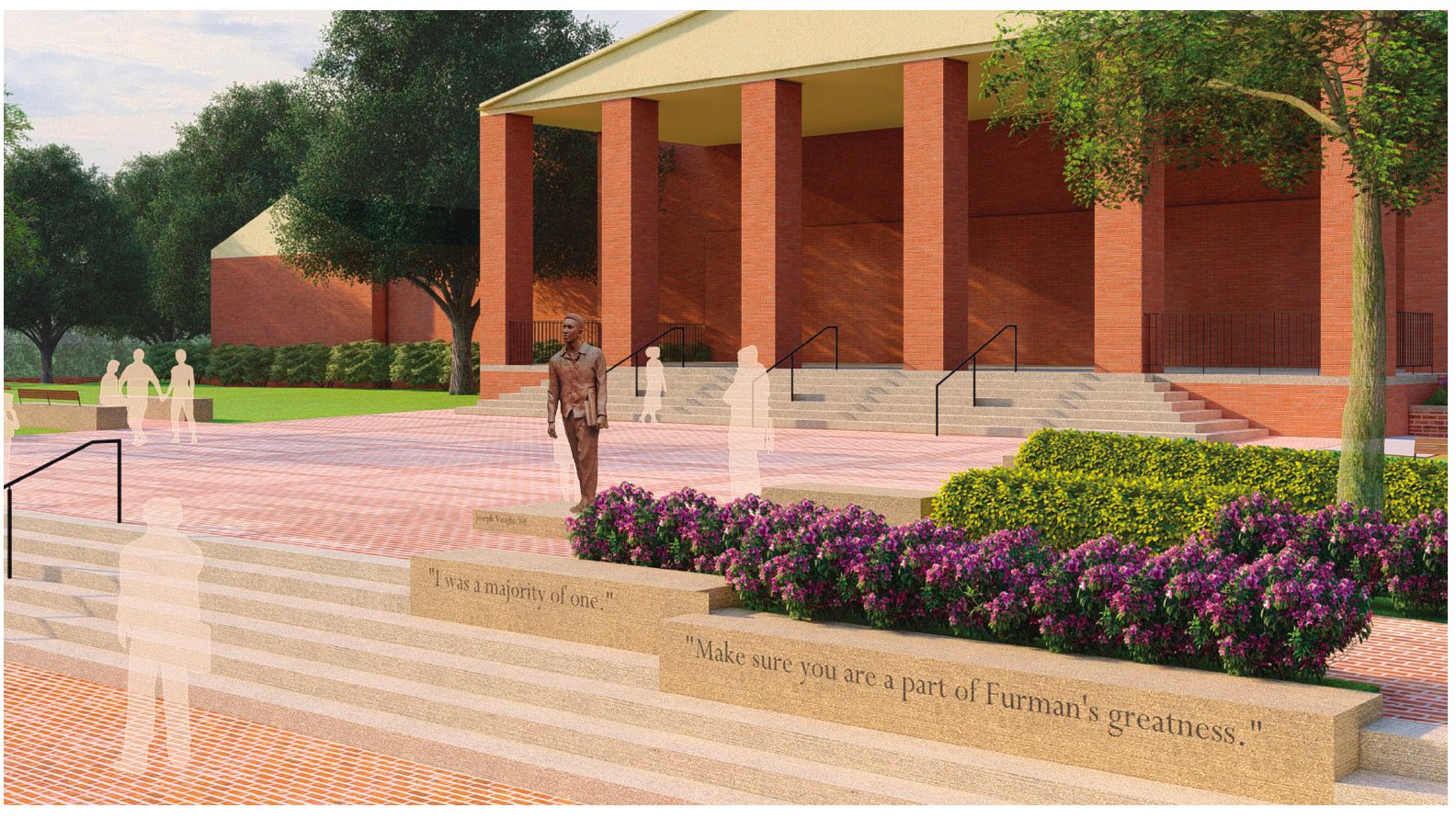

A rendering of the Joseph Vaughn Plaza that will be installed on and to the right of the front steps of the Duke Library.

Art to Love, Touch, Teach

Sculptor brings the historic courage of Joseph Vaughn ’68 to life.

By Kelley Bruss

The quiet story drew him in.

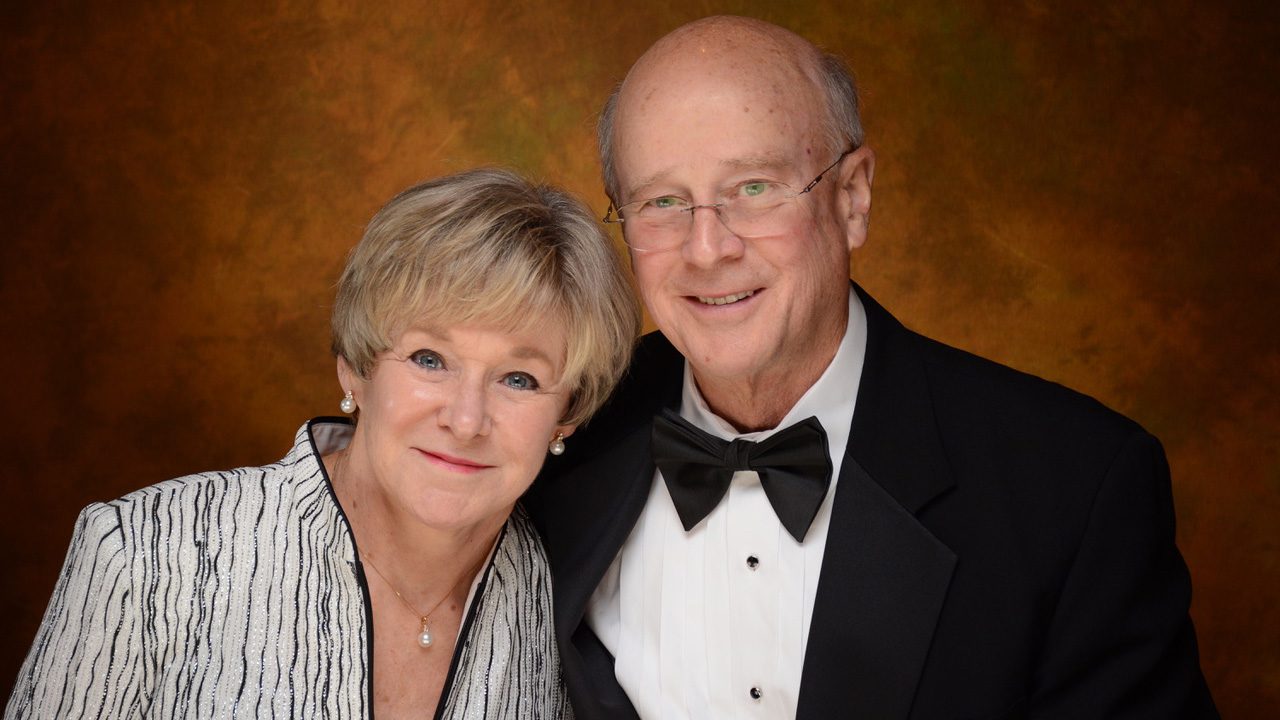

Sculptor Steven Whyte was commissioned to create a statue of Joseph Vaughn ’68, Furman’s first African American undergraduate student. A specialist in bronze portraiture, Whyte has been committed to increasing diversity in public art subjects and to art’s role as a medium to advance social justice.

The Furman project attracted him in part because Vaughn didn’t become one of the major stories of the time.

“He fit right in and took on just the role of any student,” Whyte says. “I think that speaks a lot for the university and a lot for him.”

The sculptor’s progress this spring on the Joseph Vaughn sculpture/Photo: Steven Whyte Sculpture Studios

While Whyte’s studio is in California, his work can be found around the world, on display in places such as public squares, museums, government buildings and college campuses.

The Vaughn statue “really struck me as something that could have an impact on the campus,” he says. “It’s the interaction I love, of the piece with the students.”

The statue, which is being completed this fall, is scheduled to be unveiled in January as part of Furman’s Joseph Vaughn Day activities. Whyte’s design is based on an iconic photo of Vaughn walking into the James B. Duke Library.

The statue will be slightly larger than life-size, as a true life-sized piece sometimes can look diminished in an outdoor setting or when people pose next to it for photos, Whyte says.

The statue will be the focal point of a new plaza outside the library. Landscaping and seating will finish the tribute and create space for gathering and reflection and where other pioneers who made Furman a more diverse and inclusive place may be recognized.

Whyte was trained in figurative sculpture in the United Kingdom, where he was born. His work is in London’s House of Commons; in Seoul, South Korea; in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery; throughout San Francisco and Northern California; and at the Jimmy Carter Center, to name just a few. He has completed more than 50 life-sized or larger sculptures.

“It makes me nervous when I start every one,” Whyte says, laughing.

Classically trained portraiture sculptors always begin with an almost nude figure, whether it’s a president, a celebrity or a client’s cherished family member.

By early summer, Whyte had the mockup of Vaughn’s body completed. Models began coming in – one in pleated period pants, another sporting a cardigan – to help him capture the drape and movement of Vaughn’s clothes.

Whyte uses a traditional lost-wax casting technique. After finishing the clay sculpture, he creates a negative rubber mold from it. Hot wax is poured into the mold, then covered with a ceramic shell. Next the wax is burned out and molten bronze – 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit – is poured into the cavity. Once the bronze is hard, the ceramic shell is carefully removed.

The finished sculpture of Vaughn will weigh about 320 pounds.

Whyte’s goal is to have a work in each of the 50 states. The Vaughn piece is his first to be installed in South Carolina.

To prepare for the project, Whyte attended Furman’s inaugural Joseph Vaughn Day this past January. He plans to be back on campus for the installation and unveiling early next year.

Unlike so many other kinds of art, public sculptures are often touched by passersby. Whyte can point to spots on many of his sculptures that have been rubbed to a shine.

“It’s like the love is shining the gold onto the piece,” he says.

Once a piece is installed, it’s not about the artist any longer.

Whyte shown at work on the piece/Photo: Steven Whyte Sculpture Studios

“It’s all about the relationship between the viewer and the finished piece and the lesson that piece tells,” Whyte says.

The Task Force on Slavery and Justice

The creation of the sculpture of Vaughn is among the recommendations of the “Seeking Abraham” report, which Furman’s Task Force on Slavery and Justice released in 2018, documenting the school’s early ties to slavery. The report also resulted in an increased scholarship in Vaughn’s name and the placement of markers and plaques throughout campus to tell a more complete story about the people and actions that shaped Furman.

Since receiving approval and additional recommendations from the Board of Trustees, the university has taken other actions, including removing “James C.” from Furman Hall and installing a plaque that honors the entire Furman family, noting “the diverse community of students, faculty, staff, alumni and friends who study, work and gather” on campus. The plaque acknowledges that while James C. Furman, the university’s first president and the son of its namesake, worked to build and save the university after the Civil War, he also was a vocal proponent of slavery and secession.

The board also approved changing the name of Lakeside Housing to the Clark Murphy Housing Complex in honor of Clark Murphy, an African American who worked for decades as a groundskeeper and janitor at the Greenville Woman’s College, which later merged with Furman University. A plaque placed at the front entrance of Judson Hall tells his story.