Feature

A Basketball Life

Becoming Furman’s finest player was only the start for Rushia Brown ’94.

By Ron Wagner ’93

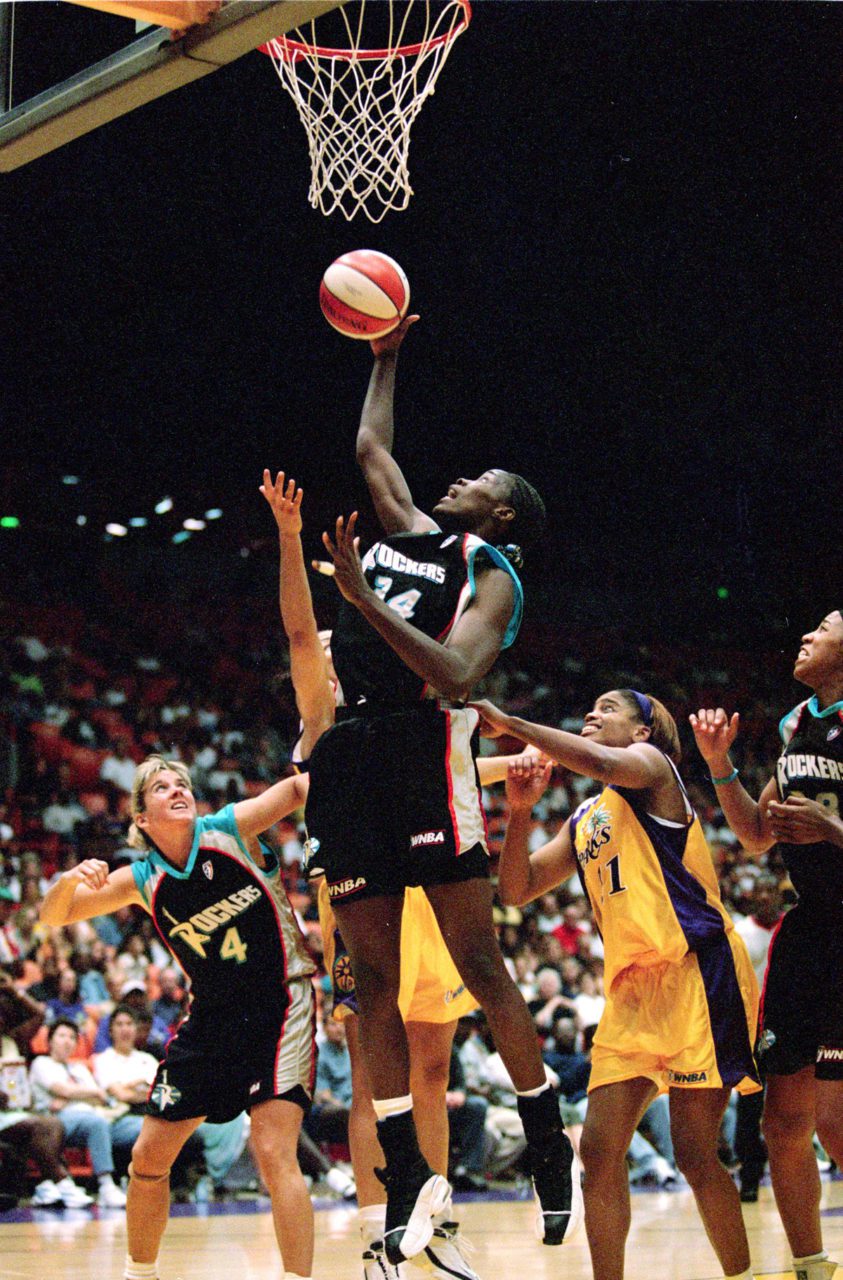

Few have overpowered the Southern Conference more than Rushia Brown ’94, the only Furman basketball player to ever compete in the WNBA. But she got a taste of her own medicine early in the league’s inaugural 1996-97 season.

Brown while playing for the Cleveland Rockers in 2000./Danny Moloshok, Getty Images.

The Cleveland Rockers were in California to take on the Los Angeles Sparks, and Rockers coach Linda Hill-MacDonald penciled Brown into the starting lineup for the first time because she thought Brown was the team’s best hope of matching up with Lisa Leslie. That would be the same 6-foot-5-inch Lisa Leslie who once scored 101 points in a half in high school, was the first woman to dunk in a game, won four Olympic gold medals, and is set to have a statue erected in her honor outside the Staples Center in Los Angeles.

Brown was somewhat less well known, but two quick baskets got Leslie’s attention.

“She was just looking at me, because I’m jumping around, I’m all excited. Then she blocked my next two shots, threw ’em in the stands,” Brown says with a laugh. “After that, I calmed down.”

Lives after retirement

There are few women – or men – who have been considered a legitimate matchup for Lisa Leslie, which by itself would make Brown one of the most accomplished Furman athletes in any sport. But that was just of one of many nights during Brown’s 10-year professional career that saw her go against the best competition in the world and propelled her into the front office of two WNBA franchises – first as player programs and franchise development manager for the WNBA’s Las Vegas Aces and, most recently, as director of community relations and youth sports for the Sparks.

With the Aces, Brown helped prepare team members for life after basketball and served as the public face of the franchise. In Los Angeles, she’ll be tasked with growing the Sparks’ presence within the community. Both positions reflect skills Brown developed after her playing days were over that may be as impressive as the ones she developed on the court.

Though they’d never even met, Aces coach and president of operations Bill Laimbeer of Detroit Pistons fame offered Brown a job with the organization based on her reputation as a nationally known motivational speaker and founder of the Women’s Professional Basketball Alumnae Association (WPBA), an organization dedicated to helping athletes create new lives for themselves after retirement.

Brown interviews Liz Cambage after a game./David Becker, Getty Images.

“One of Rushia’s greatest qualities is she likes to help people,” says Edneisha Curry, who would know. Part of the reason Curry is the only full-time assistant coach for an NCAA Division I men’s basketball team, at the University of Maine, is because Brown steered her toward the NBA assistant coaches program when she wasn’t sure which direction to go when her WNBA career ended.

A desire to help

Brown was inspired to start the WPBA after learning a one-time WNBA star was homeless. She was similarly inspired to found OverTime Basketball Academy, a nonprofit dedicated to helping girls and young women in Atlanta, when she realized many weren’t being given the foundation they needed to succeed. Her motivational speaking is also born from a desire to help by sharing lessons learned from her own struggles to transition from being a player.

“I did not know what I wanted to do, so like every other athlete, I went into a state of depression just trying to figure out who I was without the ball,” Brown says. “It was really difficult for me. But the thing that helped was I have always been a people person.”

Brown’s basketball journey started on a tragic note. She took up the sport for the first time in the 10th grade as a way to cope with the death of her father the year before. Although she rapidly developed into one of the most highly recruited players in the country, the shadow of his passing was the biggest reason she backed out of a commitment to the University of North Carolina to attend Furman.

“My family still wasn’t doing well,” says Brown, who lived in Summerville, South Carolina. “We didn’t have anything. I didn’t have a car. I just wasn’t comfortable leaving home, and Furman was close to home.”

Her place in history

Furman coach Sherry Carter never gave up on recruiting Brown, and she was rewarded with one of the biggest coups imaginable. By the time Brown was done, she had led the Paladins to their first three regular-season Southern Conference championships and set a truly staggering number of records (her name appears 137 times in the women’s basketball media guide). At 6-feet, 2-inches tall, Brown was taller than most of her competitors and also more athletic, and that fearsome combination helped her pull off the unprecedented feat of leading Furman in scoring, rebounding, steals and blocked shots all four full seasons she played, while twice being named the Edna Hartness Female Athlete of the Year.

“She is the best player other than Frank Selvy ’54 in Furman history, and I think anybody who knows anything about basketball who saw her play would have said the same thing,” says Carter, who won 300 games over 20 seasons.

Nonetheless, Brown expected her basketball days to be over when she graduated with a sociology degree, but agents representing players in Europe had other ideas. The most competitive women’s basketball in the world was played overseas, and Brown rose to the challenge to carve out a career there that saw her play in five countries and win three European titles.

Despite that success, however, had she not beaten out approximately 200 other hopefuls at an open tryout to earn a place on Cleveland’s practice squad, she may never have played in the WNBA. Once again, Brown proved she belonged, averaging 5.9 points and 3.4 rebounds over 250 games, while helping the Rockers to Eastern Conference regular-season championships in 1998 and 2001.

Not bad for someone who says she never saw her life being all about basketball.

“It was nothing I had aspired to do, but once I started playing, I wanted to be the best that I could. So every experience, every country I got to go to, every Olympian I had the opportunity to play with or against – it was just something really exciting for me, because I wasn’t supposed to be there,” Brown says. “I just wanted to go to school and get my degree and be a social worker and work with kids. In the end I’m still doing the things I want. It’s just in a different way.”