of the university

Our Oldest Stories

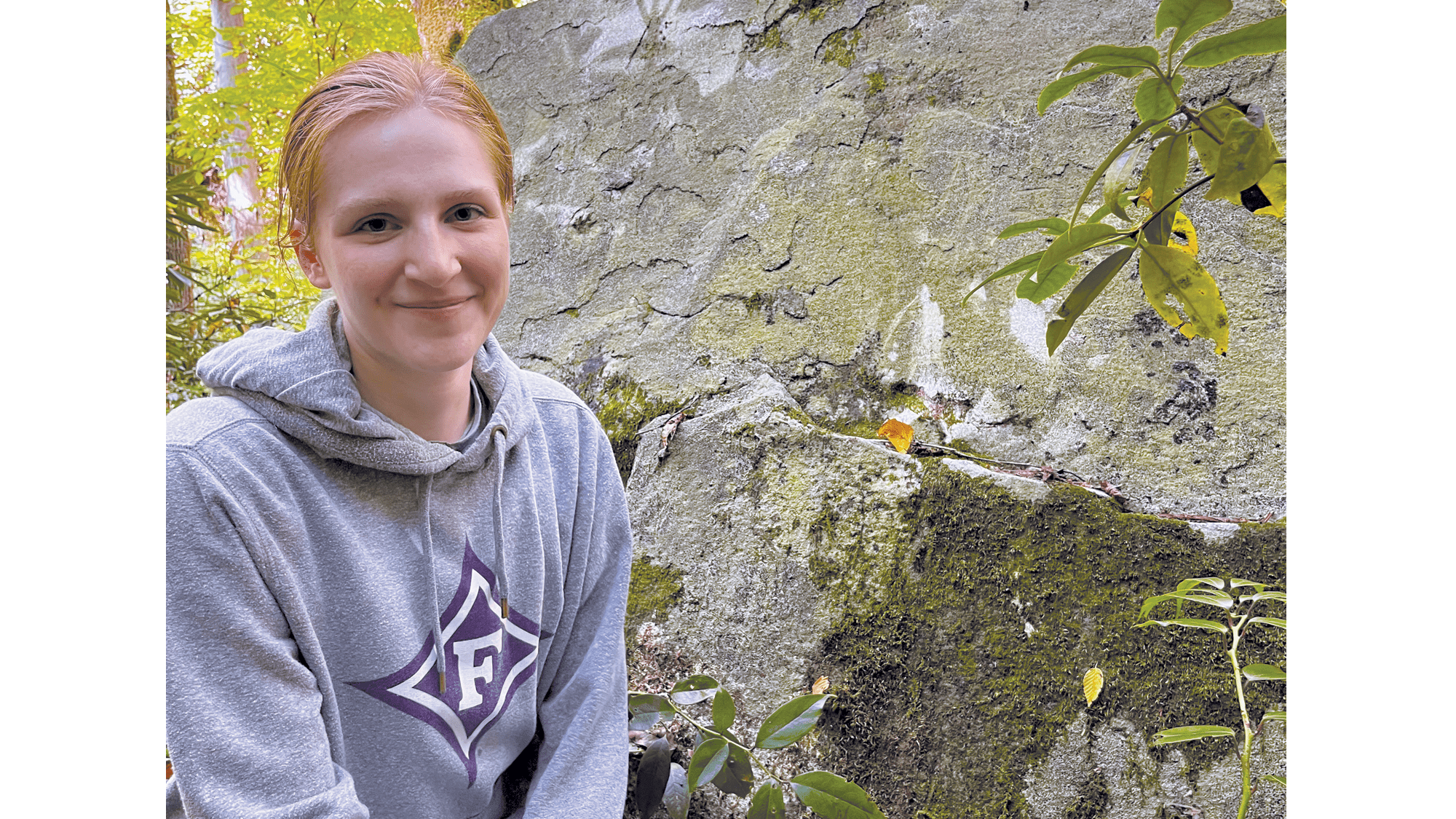

Furman Fellow Kylie Gambrill ’23 is on the hunt for patterns in the images and themes found in the ancient imagery carved and painted on rocks in South Carolina, Georgia and North Carolina.

A possible petroglyph site in Pickens County that she visited during summer research. / Courtesy photo

At the intersection of anthropology and environmental science, Kylie Gambrill ’23 encountered petroglyphs – and was captivated.

The shapes and figures carved into rocks are remnants of humanity’s oldest stories. But we haven’t always recognized their significance. “A lot of indigenous history has been erased or just not talked about,” says Gambrill.

Her senior thesis could help bring some of that unspoken history to light as she develops a database of rock imagery throughout South Carolina, Georgia and North Carolina. Gambrill worked with Andrew Womack, an assistant professor of anthropology and Asian studies, on a project exploring the history of the land on which Furman sits. She also visited the Hagood Creek Petroglyph Site at Hagood Mill, site of the only protected rock art in South Carolina and home to 32 distinct petroglyphs.

“Rock art” has been the common term, but “rock imagery” has begun to replace it, a recognition that “art” makes assumptions about the purpose of the carvings. After seeing the Hagood petroglyphs, Gambrill had to know more. And Womack was glad to supervise her research – his own field work in China had been on hold because of the pandemic.

Gambrill received one of five 2023 Furman Fellows scholarships to support her work. Her initial plan was to create a database of rock imagery sites in South Carolina, but the work expanded to include North Carolina and Georgia as well. All three states have their own records, but there was no way to study them regionally, looking for repeated images or themes. A significant part of Gambrill’s work was standardizing the data as she combined the records into a single database.

“We’re hoping to find patterns across state lines that have so far not been able to be seen because the states keep their data to themselves,” Womack says.

The new database contains records of 203 sites in the three states, including their locations, the environmental contexts of the images, and the rock types on which they are found. Gambrill also expanded her study to include pictographs, which are painted on rock instead of carved into it. And she is using digital mapping to overlay waterways, trails and other environmental features on the sites. Petroglyphs depict everything from human figures and geometric shapes to numbers and words, some of which are in recognizable languages. Some suggest maps, while others seem to be names or initials and dates.

“Early graffiti,” Womack says, smiling. Petroglyphs are notoriously difficult to date, unlike pictographs in which the paints used can offer significant evidence. But some motifs do suggest certain periods, such as the era geologists have named the Woodland Period, with dates ranging roughly from 1000 BC to 1000 AD.

Gambrill presented her research at the SoCon Undergraduate Research Forum in October of 2022 and presented again to the Society for American Archaeology in March and most recently this past April at Furman Engaged, the university’s annual engaged learning celebration open to faculty, staff, students, parents, alumni and the community.

“We’re not just studying the natural world,” says Gambrill, who hopes to someday work as an urban planner. “We’re studying how humans exist in the natural world.”