Panel discussion focuses on book about first photos of enslaved people

The pictures are captivating. Seven enslaved Black men and women look into a camera lens as they are forced to pose, mostly nude, by biologist Louis Agassiz in his quest to find evidence to support his theory that human races were created separately.

Taken in 1850 in Columbia, South Carolina, the photographs instantly became some of the most unique documents of antebellum America when they were rediscovered in the attic of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University in 1976. In the decades since, however, little was uncovered about the individual lives behind them – until now.

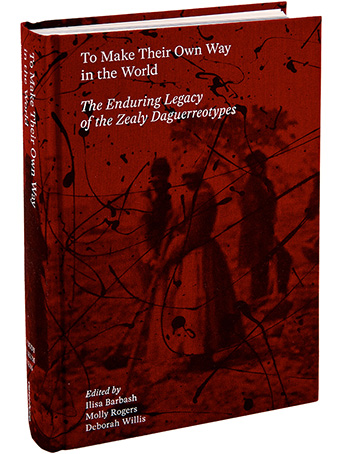

The cover of “To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes,” which includes artwork by Carrie Mae Weems, an African American artist who also contributed a photographic essay to the book collection.

On Tuesday, Oct. 6, Furman Professor of English and Department Chair Gregg Hecimovich will moderate a CLP/Furman Humanities Center panel discussion of “To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes.” Co-published by Aperture and Peabody Museum Press, the book features essays exploring the 15 images of the people through multiple academic lenses, including Hecimovich’s own.

The daguerreotype process was the first publicly available photographic process and was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s, but almost never on Black people. Hecimovich’s anchor chapter, “The Life and Times of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jim, and Renty,” uncovers groundbreaking details that bring to life the day-to-day experiences of the men and women in the pictures, which were taken by Joseph T. Zealy.

Hecimovich joined a group of prominent scholars researching the images in 2014 while a resident fellow at Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research and continued his work in collaboration with Furman students in his first-year writing seminars “Picturing Slavery.”

“When the daguerreotypes were found again in 1976, there was a little note on each one that said the name of the person and the labor camp they came from,” Hecimovich said. “Renty and Delia came from B.F. Taylor’s labor camp, so I brought students to the (South Carolina Department of Archives and History) to dig into the probate records of people associated with Taylor’s operations. We also went into the fields where we could trace their lives through old maps.”

The goal was to discover the origins of those photographed.

“How did B.F. Taylor come to possess his captives? And what were their lives like?” Hecimovich said. “We guessed that, like most enslaved people, B.F. Taylor probably inherited some of his captives from his father … and we were able to locate many of those photographed and their lost family members in the 1834 slave inventory of Thomas Taylor Sr.”

Claire Corbett ’22, a communication studies major, chose the photograph of Jack as her first-year writing seminar subject, and she and Hecimovich were able to uncover the slave inventories tracing Jack and his daughter Drana. Eventually, Hecimovich and his students reconstructed the lives behind all of the photographs by using property and tax records and with insights from slave narratives written by Charles Ball and Jacob Stroyer.

Hecimovich was able to place Ball and Stroyer on adjacent plantations, which allowed him to use the genuine experiences of these enslaved neighbors to tell the real-life stories of those originally photographed.

“Renty’s wife was likely (a woman named) Eady, and Delia seems to have had two older brothers in 1834, Hector and Caesar, and one older sister, Molly,” Hecimovich said. “July was likely Delia’s younger sister.”

Placing the photographs in their full human context is something Hecimovich found deeply moving.

Furman Professor of English and Department Chair Gregg Hecimovich.

“They’re about the only photographs of actual enslaved people, and they are just transfixing in their call to the observer, stunning in their power,” Hecimovich said. “There’s a reason enslavers didn’t photograph Black people, particularly the people they possessed – they didn’t like to think of them as human. It was only to prove a false racial prejudice that these seven people came before the lens.”

Hecimovich adds that Agassiz, who was also a creationist, failed to sway the larger scientific community to accept his ideas, despite their wide appeal in the South. It seems the pictures were shown once, in Boston in 1852.

“Agassiz was a star among scientists in America before Darwin. He had an approach that appealed to racists in the South, and he had these photographs taken because he thought he was proving that their origins were different than the origins of white people,” Hecimovich said. “There is no other record of those photographs ever being seen again until 1976.”

The preface and introduction to the book have been released through Aperture, and Hecimovich’s chapter is also available from Harvard by clicking this link. Volume editors Ilisa Barbash and Molly Rogers will join Hecimovich in the panel discussion, which begins at 4 p.m. and is sponsored by the newly established Furman Humanities Center. The public is welcome to participate in the webinar and can register here.

Furman News has made an editorial decision to not publish any of the pictures referenced in this story. More detail about the ethical debate over who owns images like these and how or even if they should be displayed is explored more fully in a recent review of the book by The New York Times.