Writing the history of desegregation at Furman

Furman’s 50 Years Commemorating Desegregation webpage does more than thoughtfully explore the University’s path to integration.

It paints a picture by presenting colorful portraits of those who blazed the sometimes turbulent path. It, too, provides perspective. A popular feature of the webpage is an interactive timeline. It begins on May 18, 1955, when Furman officials confiscated copies of The Echo, a student publication, after it published articles supporting desegregation, and runs until Jan. 29, 1965, when Joseph Vaughn officially enrolls as the school’s first African-American undergraduate student. In between are nearly two dozen historical nuggets that put the sequence of events in context.

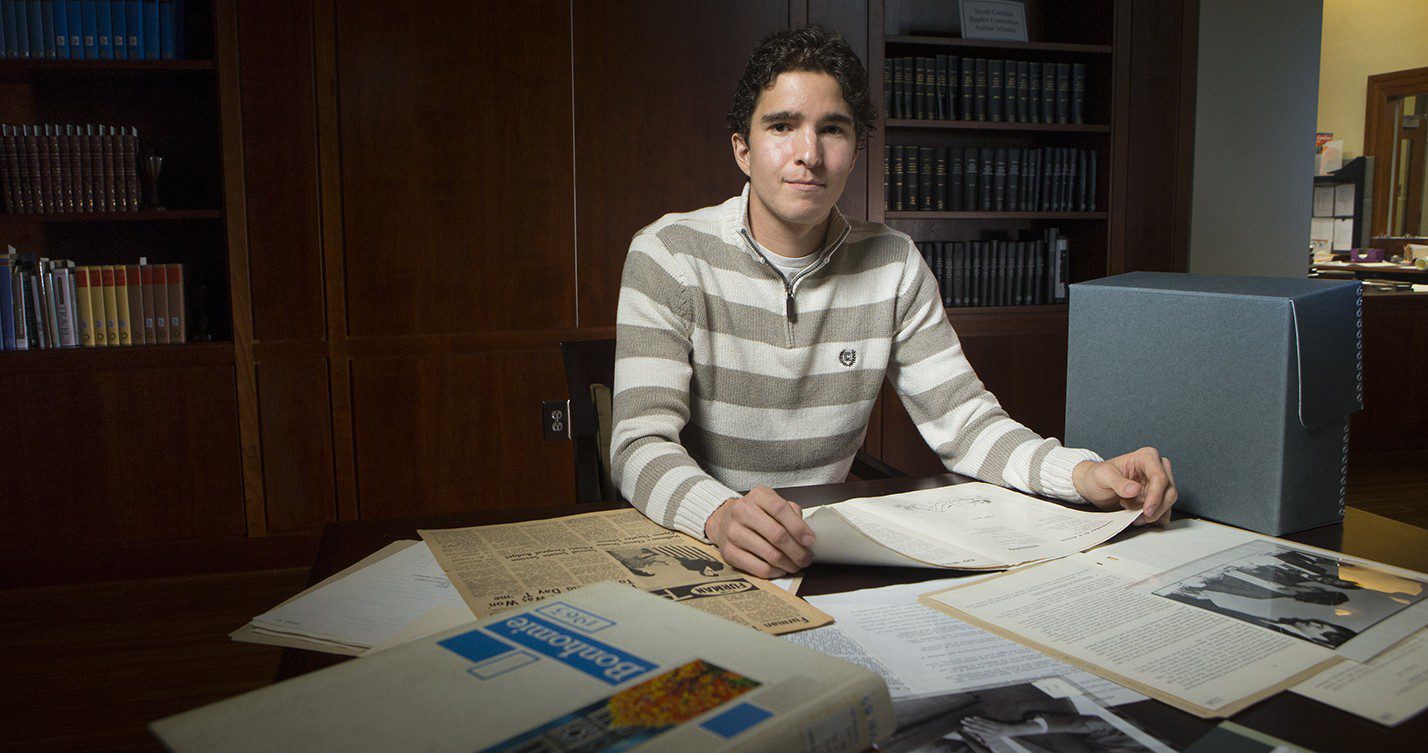

Another timeline delves even deeper, offering information about important post-integration milestones in Furman history. The comprehensive nature of the research is exactly what you’d expect from an advanced graduate student, which is exactly what Brian Neumann ’13 hopes to be some day.

As things stand at the moment, however, he’s definitely in the conversation for greatest intern of all time.

“I was alerted to some work that he was already doing as an intern in Special Collections at the Duke Library, and when I went to talk to him and he handed over some of the work he’d done I was just amazed at the care and the extent,” Furman history professor Steve O’Neill ’82, Ph.D., co-chair of a school committee charged with acquiring information in preparation for the anniversary, said.

“He basically had a 63-page annotated bibliography of almost every episode involving African Americans, the decisions of the administration that had been made about African Americans, or where African Americans had been playing prominent roles.”

It’s fair to say, in fact, that without Neumann’s contribution a great deal of what Furman thought it knew about its integration past would be lost to history. Quite an accomplishment for a self-described 19th-century historian who had little advanced knowledge or interest in Furman desegregation until DebbieLee Landi, at the time the University’s Special Collections librarian and archivist, charged him with getting a few things together in the fall of 2013.

“One of the projects that she assigned me was to start researching the history of desegregation because she knew the anniversary was coming up,” Neumann said. “Being the person that I am, once I started doing that and reading these documents I got totally immersed in the story and was absolutely fascinated by it. I think DebbieLee was expecting maybe a 20-page source guide, and pretty soon I had 400 pages of notes.”

But what could possibly be so interesting? Furman had done the moral thing and admitted a black student. A half century later, the only thing left to do was exchange back pats at the fond memory. End of story, no?

No. The University’s road to desegregation was rife with potholes. There were boardroom battles and disagreements.

“Typically, the (story) that has been told in the past has been more of a celebration of desegregation commenting on everything that Furman got right. And in fairness, we did get a lot right. But I think it’s also important to look at both sides of the issue and see how we maybe didn’t always live up to our ideals and how going forward we can better meet those ideals,” Neumann said. “When I started to look at the documents I realized it wasn’t quite a conscious policy. It was more of this 10-year long struggle and debate, and on Furman’s part a lot of reluctance and resistance to do the right thing even as the federal government and Supreme Court were pushing schools to desegregate.”

Neumann said that while Furman administrators at the time were relatively progressive for the South they were far from leaders on this issue. Neither were students, who favored keeping desegregation by large margin into the 1960s. The true visionaries were the teachers.

“What I found was it started with the professors,” Neumann said. “The faculty in the late 1950s and the early 1960s realized, hey, we have to live up to justice and equality. Discrimination is wrong.”

Neumann felt so strongly about what he learned that he wrote a paper. On the same page is a link to a doctoral dissertation written by Courtney Tollison ’99, Ph.D., now an assistant professor of history at Furman.

Tollison’s paper was one of the first serious looks at Furman desegregation, and in some ways Neumann’s conclusions stand in contrast to hers. Neumann asserts the most important thing is having access to the information.

“One of the things I’m glad Steve O’Neill did with the desegregation project is he changed the wording of the project from a ‘celebration’ of desegregation to a ‘commemoration,’” Neumann said. “I think a celebration is emotional and uncritical, and while there is value to it, it doesn’t allow us to fully understand the complexities of an event…whereas a commemoration really allows you to engage with the event, ask difficult questions, accept difficult answers. It’s messier, but I also think it’s more meaningful.”

O’Neill, whose scholarly focus is the American South and South Carolina history, never taught Neumann, but he is the first to admit his contributions are just this side of invaluable.

“He started out as a research assistant but very quickly became a peer of mine. I just had to get out of his way, and he really did a remarkable job not only writing the piece that was published but in doing a whole bunch of other things that we had not anticipated in terms of tracking down photos, editing, and writing for the website,” O’Neill said. “His work on the calendar—it wouldn’t have been done without him. And I can say the same thing about the booklet . . . I knew that he was at the top of the list of history majors who graduated in 2013, but I was not prepared for the quality of work he was able to produce. And the final result really speaks for itself.”

Neumann will present his work both to Furman and the South Carolina Upcountry Museum in the coming months. He calls it an “immense honor,” which it is. It’s also a chance to use history to advance a future that clearly needs some more advancing in light of the racial tension that continues to plague America.

“It’s important to remember that hundreds of Furman students and professors wrote letters, gave speeches, and signed petitions in support of desegregation. And it’s important to remember that Furman desegregated peacefully and voluntarily, and against the wishes of the Southern Baptist Church,” he said. “But it’s also important to remember that Furman desegregated only once it had no other choice—once political and economic pressure made it unavoidable.”