Unraveling history by way of plants

If you read “Historical Botany in the Carolinas” and erroneously thought “science,” you’re not alone—so did the Andrew Mellon Foundation. May X and preconceptions sometimes don’t get along, but Furman’s Chris Blackwell is happy to mend fences.

“Mellon doesn’t fund science,” Blackwell, the Louis G. Forgione University Professor of Classics and class creator, said. “But this is a set of questions that you will never get to answer if you take a purely scientific approach to them. This is a liberal arts problem because it’s a problem of science, it’s a problem of history, and it’s a problem of language because these guys were naming plants back before there were standard names for plants . . . We had particular arguments about how the data related to identification of plant specimens ought to be captured, which is different from what the regular biologists tend to do, and they have failed to notice that what they do has never worked.”

That sales pitch was enough to convince the Mellon Foundation that the work Blackwell and his class were doing met its higher education and scholarship program requirements, resulting in “$50,000 to experiment with work on historical botany as a liberal arts project,” Blackwell said. “These guys” were the first English and French settlers on the east coast of North America, and many of the plant species they documented can still be found in European museums.

Blackwell and his wife, Amy, who owns a Ph.D. in plant and environmental science from Clemson, ran across some of these displays during a visit to the National History Museum in London and were surprised to see that many had been plucked from South Carolina in the early 1700s. With that, the seeds for a May X were planted. Pun intended.

“Because of my work (with) dead languages and manuscripts I’m really interested in grammar and language and syntax, which is the same kind of data-organization problem. How can you capture relationships among things where you might have many different views of what that relationship means?” Blackwell said. “It is a mistake to treat this identification as an actual description. It’s much more like a series of commentaries where people have different opinions, and peoples’ opinions change over time. You may think the old guys are wrong, but you don’t want to get rid of that.”

Kara DeGroote ’16, a biology major, signed up for the class because it represented an opportunity to do plant research. She also got a crash course in how much the English language has changed over the past few centuries.

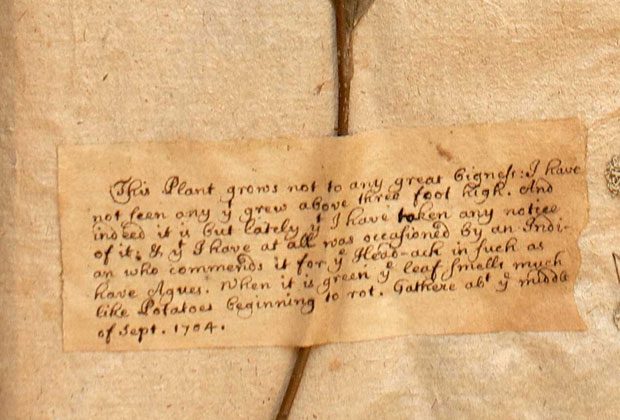

“They use f’s where you would normally have s’s” she said recently in a Plyler Hall biology classroom, taking a break from pouring over the Blackwells’ photographs of 300-year-old plant exhibits. DeGroote was organizing, editing, and linking the texts to add to a database while pursuing her own exploration into Sir Hans Sloane’s collection of plants.

“I’m going to go through all of his labels to research all of the ones that he talks about having anything to do with medical uses to see if the ones he thought could be used for medical purposes can still be used for medical purposes or if other people have found similar things,” she said.

Sloane procured many of his South Carolina specimens from Joseph Lord, a minister who lived in what was once Dorchester, S.C., but is now an archaeological site near Charleston. Blackwell took his students there as well as the South Carolina Botanical Garden and the Oconee Station State Historic Site.

“From a scientific point of view this is like a field survey. If you want to study what’s going on in the environment now you go to an area and see what plants are there and you go back in 10 years and see what’s changed. Well, this is like being able to go back 300 years and do a field survey of Dorchester, South Carolina,” he said. “I tell the students (these old exhibits) are archaeology, but a really nice kind of archaeology where you stay inside and not some sun-baked Greek hell hole and you already know you found something.”

The class spawned DeGroote’s project as well as others as diverse as mapping of where various plant species are growing, research into why Lord moved his family from Massachusetts to South Carolina in the first place, and a comparison of specimens from different collectors and their origins. In other words, exactly the type of creativity Furman’s May Experience is supposed to foster.

“Our biggest accomplishment was getting the Natural History Museum not only to let us take pictures but put them out under an open license so that anybody else can take them and reuse them. Our purpose here is not to get our data up on our Web site. Our purpose is to get our data up on everybody else’s Web site. That’s scholarship,” Blackwell said. “This is engaged learning. It’s not just banners (at Furman). I think we really mean it.”