In the heat of battle against COVID-19

Sue Shugart ’88 with colleagues on the night shift at KershawHealth. The hospital had one of South Carolina’s first two COVID-19 patients, and the town of Camden became the first area with community spread.

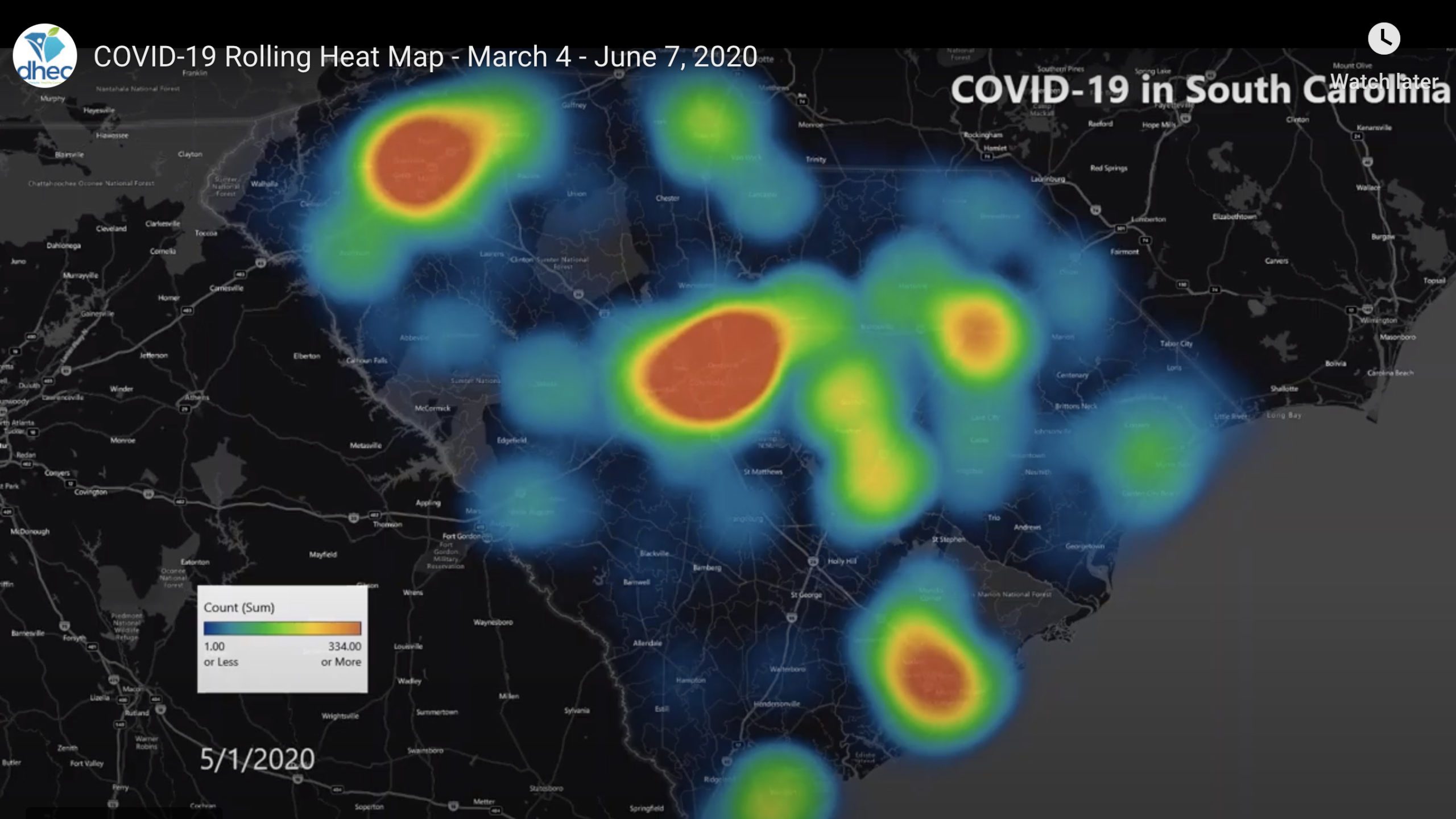

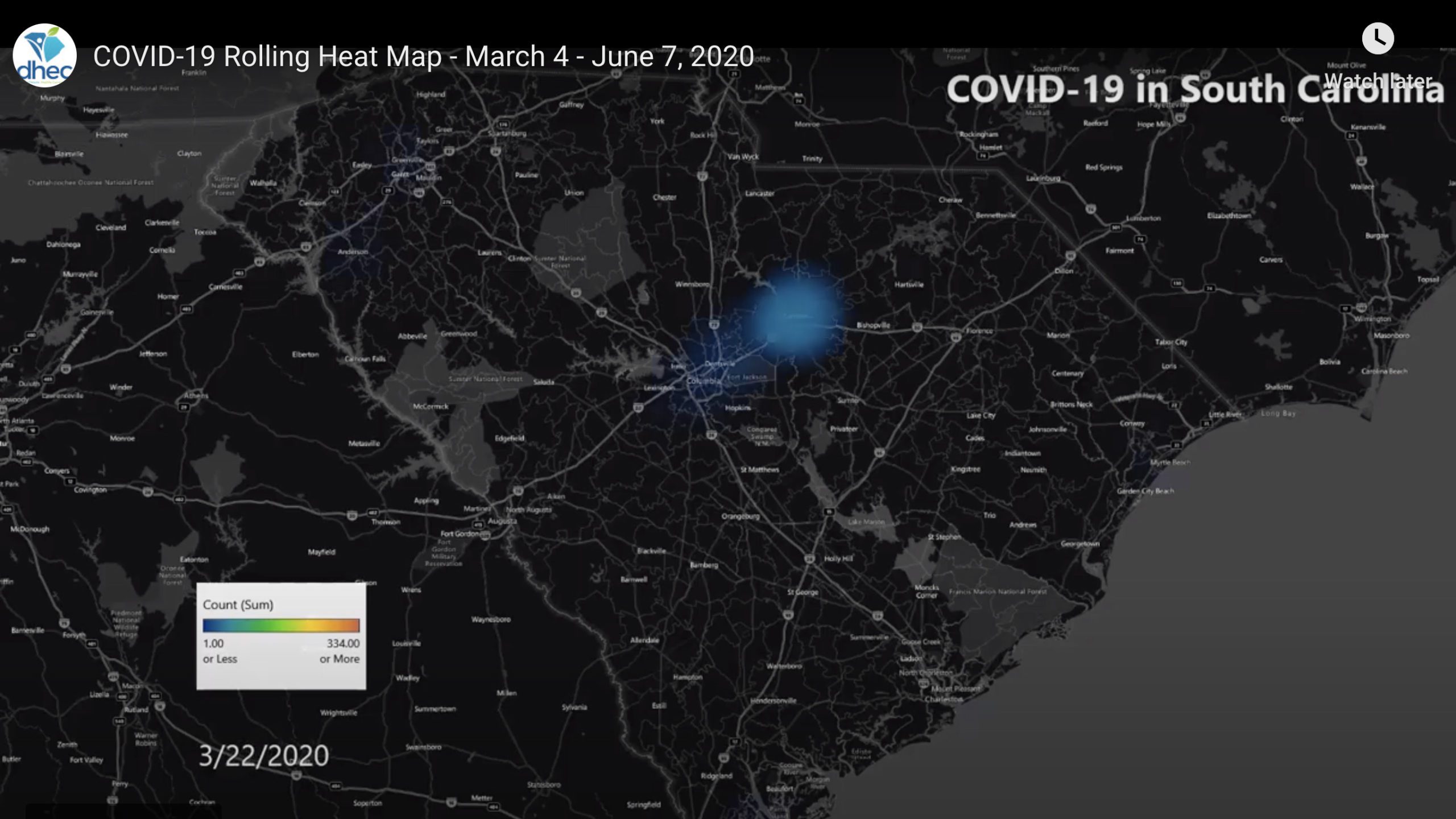

On a heat map of South Carolina, COVID-19 first appears as a dim blue dot over the city of Camden that swells and turns green, and as other dots start to appear across the state, the cloud over Camden, in Kershaw County, erupts and billows into a yellow mass that turns red, like a deadly storm moving across a weather radar.

The original dim blue dot was a patient admitted to KershawHealth for respiratory symptoms but who did not meet the then-current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for suspicion of the novel coronavirus. On the second day in the hospital, the patient wasn’t responding to therapy, and her physician became suspicious that COVID-19 was also a factor. The next day, after prodding by the hospital’s infectious disease specialist, a skeptical state lab tested the patient for COVID-19.

On March 6, the test came back positive. It was the state’s second confirmed COVID-19 test; the other was for a person in Charleston County who had traveled to France and Italy, where the pandemic was widespread.

“We were off to the races,” says Sue Shugart ’88, a veteran healthcare leader who was just seven months into her role as chief executive of KershawHealth.

Within days, several KershawHealth patients tested positive COVID, and the state health department said Camden was likely experiencing “community spread,” meaning the source was unknown, “and the risk of spread to other communities is possible, as seen in other states across the country.”

Shugart’s team established a COVID ward, which filled quickly, so they doubled its size. Soon, every ventilator the hospital owned, and every vent it had borrowed, was in use, and some patients had to be transferred to larger hospitals. At the peak, patients in more than 30% of the hospital’s 70 staffed beds were suffering from or suspected of having COVID-19.

On April 7, a “home-or-work” order went into effect across South Carolina. People started social distancing and the siege lifted.

“We made it through,” Shugart says. Her hospital had tested 1,000 patients for COVID-19 and treated 144. Eleven patients died; three while hospitalized at KershawHealth and eight after being transferred to other hospitals.

Asked if the pandemic was the hardest challenge she’s faced as a healthcare executive, Shugart says, “I sure hope so. I don’t want anything more challenging.”

Shugart handled her hospital’s crisis with leadership skills she honed as an English major and a student leader at Furman. She was vice president of student government, a member of Senior Order and Omicron Delta Kappa (and a recipient of the ODK’s Winston Babb Memorial Award), and she served on the admissions advisory council.

Communication, transparency, building trust and being present for her staff during long hours all helped Shugart navigate through the COVID crisis. She walked the hospital checking on staff several times a day, especially at night before she went home.

One of the hardest moments came at 10:30 one night, when she told staff on a medical nursing unit that they had been exposed to COVID. But Shugart still needed them to come to work every day – and some who were home quarantining had to return – under new precautionary guidelines from the CDC. “Or else we couldn’t operate the hospital.”

She was supposed to return to Furman as a member of the Spring 2020 class of The Riley Institute’s Diversity Leadership Institute. Shugart attended two meetings; the third was scheduled for March 12, when her hospital was in the throes of COVID-19.

She emailed Riley Institute Director Don Gordon, on May 1, apologizing for having to drop out. “As I prepare to leave the hospital tonight, I am not planning to come in for the next two days,” she wrote. “And that will be the first time I can say that since March 4!”

As a Furman student, Shugart says she developed critical thinking skills, and she learned to “understand other perspectives and to see myself through a different lens.” She also learned to recognize her own biases, something she hadn’t encountered before. “Most of that happened in my coursework and with my professors that I’m still grateful for.

She’s using those skills to better understand, and draw attention to, social determinants of health outcomes. People of color face greater challenges in health care, from increased risks of chronic diseases and higher death rates, to shortages of healthcare providers of color.

According to a paper published May 11 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “African American individuals and, to a lesser extent, Latino individuals bear a disproportionate burden of COVID-19–related outcomes. The pandemic has shone a spotlight on health disparities and created an opportunity to address the causes underlying these inequities.”

Shugart saw this first-hand. “We saw how patients were fairing. We noticed (the disparity) before it made national news,” she says. “How we go about solving the disparity, it’s even more important to me now.”

It’s also important to clear up misconceptions about the pandemic.

“It’s not the flu,” she says. Everything about COVID-19 is novel. There is no evidence-based medicine for COVID because there is no previous evidence. She worried about her staff becoming infected from being in the community (a handful did). She worries still about the eagerness for people to gather in public, especially in a Southern town steeped in Sunday church traditions.

The state health department publishes a rolling heat map every two weeks. On June 2, the map still showed blue and green blotches festering over most of South Carolina, with angry red and yellow clouds persisting over Greenville, Columbia, Florence and Charleston.

“If people really understood that the measures are supportive,” not curative, Shugart says, wishfully. “In the U.S. we’ve become accustomed to knowing there’s a pill to fix it or a surgery to fix it no matter the medical problem.”

Not for COVID-19. Not yet.