From The Vault

Furman’s Nuclear Reactor?

It was once a distinct possibility.

By Jeffrey Makala

Associate Director for Special Collections and University Archivist

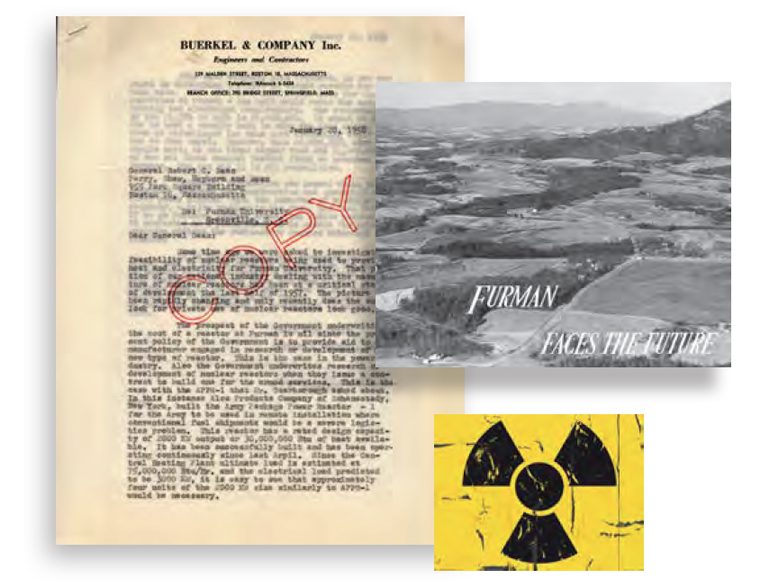

The 1950s were an optimistic period at Furman. Early in the decade, the university acquired a series of adjoining land parcels north of Greenville totaling 973 acres. We then engaged the most prestigious university architects in the country – Perry, Shaw, Hepburn and Dean of Boston – to design a master plan for a new campus and see it through to construction. For the first time, Furman would have a spacious, coed, residential campus with the most modern accommodations, facilities, laboratories and room to grow.

Every detail about the design and components of the new campus was open for discussion, from large-scale decisions such as the layout and size of different buildings on the site to more modest details such as fencing, landscaping and walkways, and designs for specific light fixtures. Many initial thoughts were (thankfully?) not realized. There was a fleeting idea to build a bowling alley in the basement of the library instead of the athletic building (which would become the Physical Activities Center), and Furman also entertained having an indoor ice rink attached to the athletic center.

One benefit of having Perry, Shaw, Hepburn and Dean on board was the firm’s wide range of connections. When the Charles Bulfinch-designed Boston State House was being remodeled in the mid-1950s, the architects were able to secure two large brass chandeliers from it that dated back to its construction in 1798. Would Furman be interested, they asked in a letter to President John Plyler? Yes, said Plyler in 1957, writing back, “I do hope they were able to get the old fixtures from the State House.” Today these two 18th-century chandeliers hang in the library’s Pitts and Haynsworth rooms.

By 1956, discussions turned to choosing individual heating and cooling systems for Furman’s buildings or constructing a central heating plant for the whole campus. The initial estimate for an oil-powered central heating plant was $1 million and quickly grew to $1.2 million in the succeeding years as construction proceeded. A coal-burning plant was briefly considered as an oil plant was more expensive to build. But an oil-burning plant had the advantage of being easily switched over to natural gas if, in the future, gas became a more cost-effective fuel source.

While exploring options, architect Robert Dean solicited a comprehensive energy report from the Boston engineering firm of Buerkel & Co. They reported back, in January 1958, that Furman could purchase a small nuclear reactor to provide heat and electricity for the campus.

“Only recently does the outlook for private use of nuclear reactors look good,” they reported. Because there were no federal grants available, Furman would have to pay for the reactor. A private company could supply a 14,500-kilowatt unit, sufficient for Furman’s needs, for a cost of $6 million. And, they reported, insurance coverage for accidents at privately owned nuclear reactors was now available, so the prospects looked favorable. But at six times the budgeted cost, Furman could not justify it.

The firm concluded by saying Furman should revisit the question in three years, when conditions and pricing may be more favorable, and architect Robert Dean agreed. Furman, alas, would not purchase its own nuclear reactor, and would instead use oil heat and local electricity.

Students from Africa invited their classmates to see their respective home countries, in some cases for the first time.