Feature

On His Own Terms

How Thomas Rain Crowe ’72, one of Furman’s greatest literary forces, found his voice.

By Kelley Bruss

Thomas Rain Crowe ’72 traces his life as a writer back to California, his time as a “Baby Beat” learning from the first generation of Beat poets.

“I got my real literary education in the streets of San Francisco,” he says.

But it was the solitude of the Appalachians, not city life, that carved deepest onto who he is as both a person and a poet. He found his writing voice while living in a cabin, growing his own food, leaving hardly a trace on society’s grid.

“Finally, I wasn’t copying other people, and I liked what I was writing about,” Crowe says. “Nature.”

As a poet, novelist, essayist, translator, editor, publisher and recording artist, he is the author of more than 30 books.

“He’s basically been able to be an artist entirely on his own, consistent terms,” says Jeffrey Makala, Furman’s special collections librarian and university archivist, who describes Crowe as “one of Furman’s strongest literary forces.”

Furman’s library holds copies of all of Crowe’s published writings, donated by his partner, Nan Watkins, as well as letters he wrote to his parents during his years at Furman. The remainder of Crowe’s papers were acquired by Duke University.

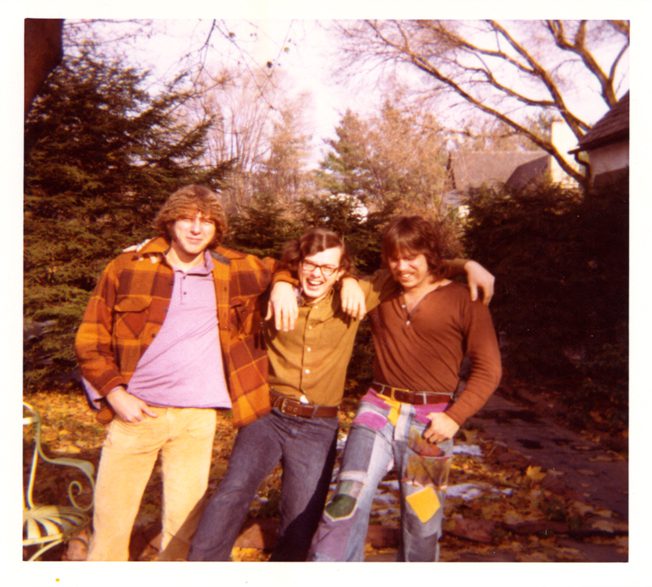

Stephen Zerbst ’72, David Tunstall ’72 and Crowe, photographed in 1970.

‘Answers in the ponds’*

Crowe’s family moved frequently, but enough of his childhood was spent in the Southern Appalachians that he considered the mountains home.

Just before his senior year of high school, the family moved to Pennsylvania, within reach of New York City. Crowe explored Greenwich Village, buying loud pants and collecting new ideas about music, words and life. But even with the pulse of New York in his ears, he wanted to go back to his mountains for college, and Furman was closest to those mountains.

“I went to Furman sight unseen and I didn’t do any research,” he says.

In fact, Furman of the late 1960s was deeply connected to the Southern Baptist Convention. Crowe’s newfound ideas –about music, drugs, war and sex –were out of sync, to put it mildly.

But the reason he’d picked Furman ended up being sound.

“There were things that kept me there and I could focus on,” he says.

The main thing? Trips into the mountains near Saluda, North Carolina. He and a friend wandered the forests and found themselves in the front yard of Walter Johnson, who lived alone in a cabin by a pond.

The chance meeting would lead to one of Crowe’s most acclaimed books. But at the time, all he knew was that he wanted to live like Johnson.

“I fell in love with that place and with the lifestyle,” he says.

‘The drunken binge of boulevards and city streets’*

Crowe had been writing poetry since he was young. By the time he finished at Furman, he’d decided to become a poet. What’s more, he says with a laugh, “I decided that to be a great poet, you had to be French.”

He moved to France, taking jobs where he found them: Paris, Grenoble, Bordeaux, Brittany. But after a year, he realized he belonged back across the ocean. It wasn’t the American culture he missed, it was the land.

Crowe made his way to San Francisco and the mecca of the Beat culture, City Lights Bookstore. Poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti was the first person he saw when he walked in the door.

“He was my hero,” Crowe says. “Here was a guy writing in a contemporary language about modern subjects –taboos, even.”

Crowe had landed at the epicenter of the “San Francisco Renaissance,” an explosive period for literature, art and music. He was part of the team that resurrected Beatitude Magazine, which had originally published the Beat poets. And he organized what would become an institution, the first San Francisco International Poetry Festival at Ferlinghetti’s request, helping to fill a 2,000-seat auditorium to overflowing on both nights.

“I was just happy being around my heroes,” he says.

Crowe eventually left the buzz of city life for a year in the Sierra Nevada mountains. He lived in a tipi on ceremonial land with a community that had included the Maidu people and began to develop a deeper awareness of ecological and bioregional issues – ideas that meshed with what he already felt about the mountains on the other side of the continent.

Crowe walking up the stairs of the James B. Duke Library.

‘I set down my bags’*

Death brought him back to those mountains. Johnson, the old man from his Furman days, was gone and the owner of the property invited Crowe to stay in his cabin.

He came back to spend a winter there, read Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden” and asked himself whether he could live outside the boundaries of civilization.

Crowe spent four years, from 1979 to 1982, off the grid. He grew or scavenged his food. He slept and woke with the sun. He made wooden stools and sold them in town to get cash for the items he couldn’t make or grow: salt, for example, or oil for his lamps.

He filled journals with poetry and reflections on the world around him, which he felt he was finally beginning to understand. He also chose a new name.

Crowe was born Thomas Dawson.

“I didn’t think I had a poet’s name,” he says. “Tom Dawson. It’s like falling off a cliff.”

He liked the lyrical feel of three names: Ralph Waldo Emerson, for example, or John Crowe Ransom. A childhood friend, David Crowe, had introduced him to the Cherokee expression “rain crow.”

“I didn’t want to be an Indian. I didn’t want to be a bird. But it worked for me,” says Crowe. Crowe moved to Jackson County and took a job in a newspaper print shop to pay his bills. But he was ready to write in earnest.

“I started seeing that I had a lot of material and it was time,” he says.

He began New Native Press, publishing some of his own work and that of his San Francisco Baby Beat friends. He turned his journals from the cabin years into the award-winning book, “Zoro’s Field,” a work that touches on deep ecology, the changing seasons, stillness and observation of the natural world.

“Furman prides itself on sustainability now,” says Makala. “But Thomas was thinking about it and practicing it in deep, meaningful ways before it was even coined as a term.”

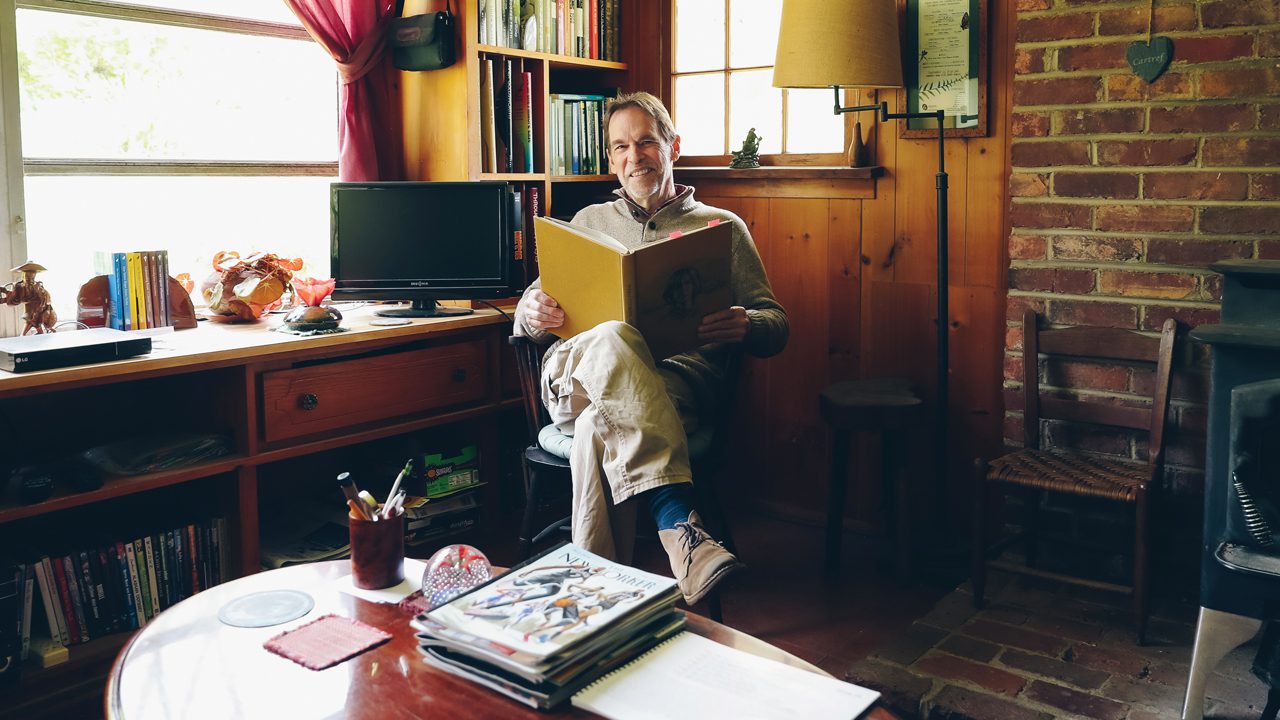

Crowe, a poet, novelist, essayist, translator, editor, publisher, recording artist and author of more than 30 books, at home in his study.

‘I have grown old sitting here’*

Crowe hasn’t stopped writing. He finished a science fiction novel during quarantine in 2020. But he’s also spent much of his time in recent years translating works from around the world and across the centuries.

One of his favorites is Yvan Goll, who wrote poetry in French, German and English in the first half of the 20th century.

More recently, Crowe has been bringing Hafiz, a Persian Sufi poet of the 1300s, to modern readers.

They’re not translations in the strictest sense. Crowe uses English translations to create versions that incorporate more of the meter and rhythm and sometimes even rhyme that would have been in the original Farsi.

“The way that the ancient Sufis write is so beautiful, and I’ve tried to unearth that beauty in my versions,” he says.

It seems perfectly natural to him that his literary career has landed here, now.

The expression “follow your bliss” took hold when he was a young man. “That resonated with me because I was good at it. I’d get an idea and I’d do it.”

*All subheadings are taken from “Crack Light,” a 2011 collection of Crowe’s poetry. The poems quoted include “A Pond in the Woods,” “The Country,” “In Permanence” and “Love.”