Feature

Birdsong: Hearing New Opportunities

Walk outside and listen. What do you hear?

By Clinton Colmenares

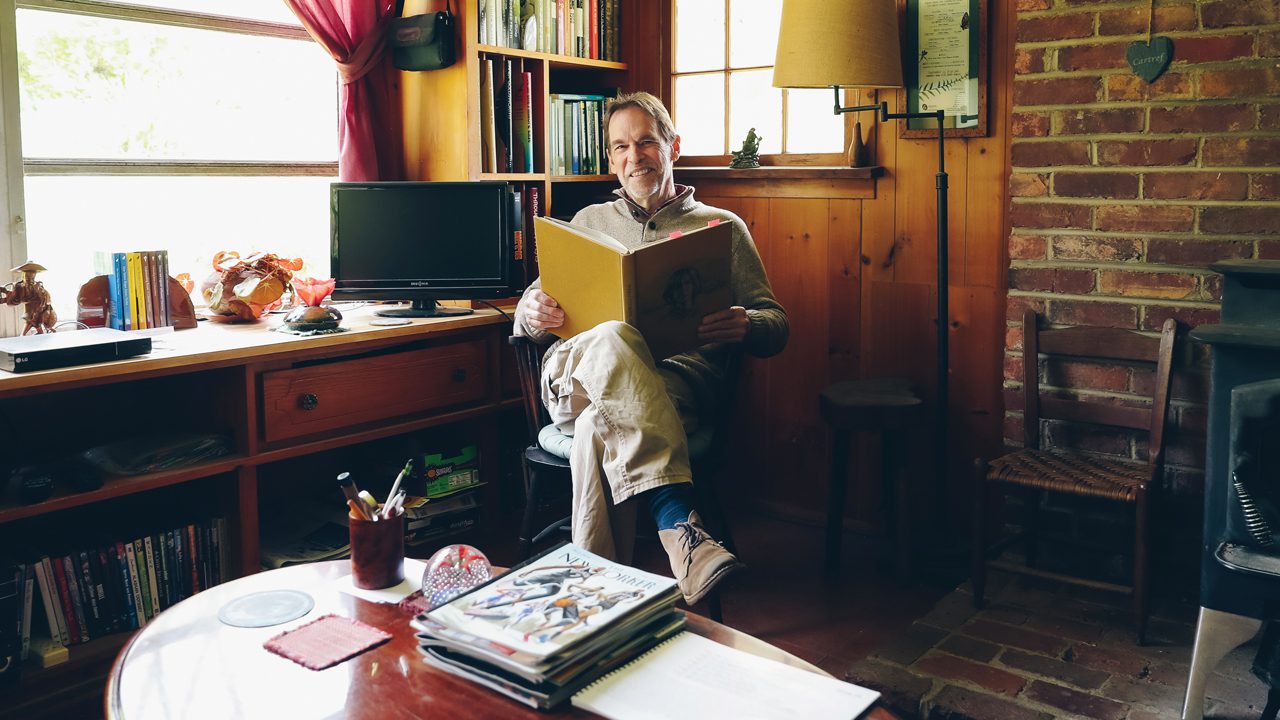

Associate Professor of Biology John Quinn looks for birds at Greenbrier Farms in Easley, South Carolina.

If you’re with John Quinn, you’ll become aware of the calls of songbirds that make up a soundscape of a field, the teakettle teakettle teakettle of the Carolina wren, the Eastern meadowlark’s flutelike call, the rowdy jeer of blue jays and the whistle of the field sparrow that has been likened to the sound of a dropped ping-pong ball.

Quinn can’t help but notice the distinct sounds. Birds are part of his being, literally and figuratively, from birding with his father in his boyhood Minnesota to the winged meadowlarks and wrens tattooed on his arm and torso. But as a conservation biologist, Quinn hears more than bird calls in the tweets and whistles and songs of his feathered friends–he hears opportunity: the potential to rethink farming and ranching practices in ways that transform ecology and recast agricultural goods.

“So often, farms are seen as only producing food,” says Quinn, associate professor of biology at Furman. He and other ecologists are trying to change that concept.

Globally, farms make up 39% of all land use, Quinn says. But farms can produce more than food and fodder. Through regenerative agriculture, a conservation approach to land use, farms can help produce clean water, capture carbon and support biodiversity, all contributing to healthier flora and fauna.

But how do you know when a farm is healthy? One way is to track the number of different bird species on a farm. That’s where Quinn comes in. When it comes to counting crows and wrens and larks, his research is more about bird listening than bird watching.

Quinn deploys his recording units at Greenbrier Farms in Easley, South Carolina, to collect acoustic and soundscape data to measure how regenerative agriculture affects bird diversity.

In 2020, Quinn teamed up with General Mills, which has a goal of increasing the footprint of sustainable or regenerative farms, to use automatic recording devices on 39 farms in Kansas, where farms make up close to 90% of all land use. From May 1, 2020,until January 1, 2021, the devices, which he shipped from Furman, recorded 7 terabytes of data. Quinn is processing all of this data with the help of machine learning, careful listening, and undergraduate students in his research methods class and with summer research students Emilia Hyland ’21, Annie Schulz ’22, Sydney McManus ’23 and Ian McPherson ’23.

Back in his lab at Furman, Quinn pulls up a sound file from one farm that doesn’t practice regenerative agriculture. It’s eerily quiet.

Then he pulls up a file from a different farm that erupts in a symphony of sounds from dozens of birds, from bobwhite quail to ring-necked pheasants to crows and lots of little bird sounds chirping away. Simply by listening to the file, Quinn can tell that the second farm provides more biodiversity by growing cover crops, leaving grass strips where birds can nest and forage, including wind breaks and generally attracting a large and diverse population of birds.

“We couldn’t and shouldn’t expect farmers to only be rewarded for producing food,” Quinn says. Farms can market their biodiversity efforts and claim a premium for their efforts.

“The farm can say, ‘Look, this is great beef, this is great corn, but also by supporting my farm, you’re also supporting these other externalities,’” like carbon sequestration or wildlife diversity.

On the other hand, when farmers are only remunerated for the biomass they produce, costs to the environment, like repairing degraded streams and watersheds and contributing to global warming get lost.

“When you buy a hamburger you’re not currently paying the (environmental) cost of corn,” he says. So why not incentivize farmers for making better use of their lands?

Birds would appreciate it. They need all the help they can get. Meadowlarks and grasshopper sparrows are grassland birds whose populations have declined by about 50% in the last 40 years, Quinn says.

Land conservation areas, like protected conservation easements and national and state parks and forests, make up only about 15% of the planet.

Quinn calls birds a gateway species, providing an entry into other conservation topics.

“If we do a summer’s worth of research and give farmers a list of birds we heard on their farms, they’re like, ‘Wow, I had no idea that was on my land.’ Then in future years, they’re much more inclined to adopt practices like rotational grazing or cover crops, or to mow later to protect ground-nesting birds,” he says.

Quinn directs his companions to a bird sighting.

His work has also benefited Upstate farms. About five years ago Quinn and colleagues worked with Greenbrier Farms in Pickens County to restore their forest understory with sustainable, regenerative grazing practices. Quinn used automated recording devices he’s now using in the Midwest to determine if the bird communities changed.

This spring, in an extension of the work with General Mills, Quinn sent dozens more recorders back to farms in Kansas and to Michigan, and he expanded internationally to farms in Saskatchewan and Manitoba in Canada.

The work not only informs General Mills’ farming practices, but Quinn and his students will publish peer-reviewed research papers, adding to the scientific understanding of using recording devices to perform assessments and of the benefits of regenerative farming practices to birds.

“There is growing recognition in the U.S. and globally that conservation beyond protected areas is fundamental,” Quinn says. “We can’t tell farmers how to manage their land, but if we can give them something to think about, it goes a long way.”