Feature

The Athlete Architect

Can you design a great football player? For health sciences professor Tony Caterisano, 29 years of player data offer a blueprint.

By Vince Moore

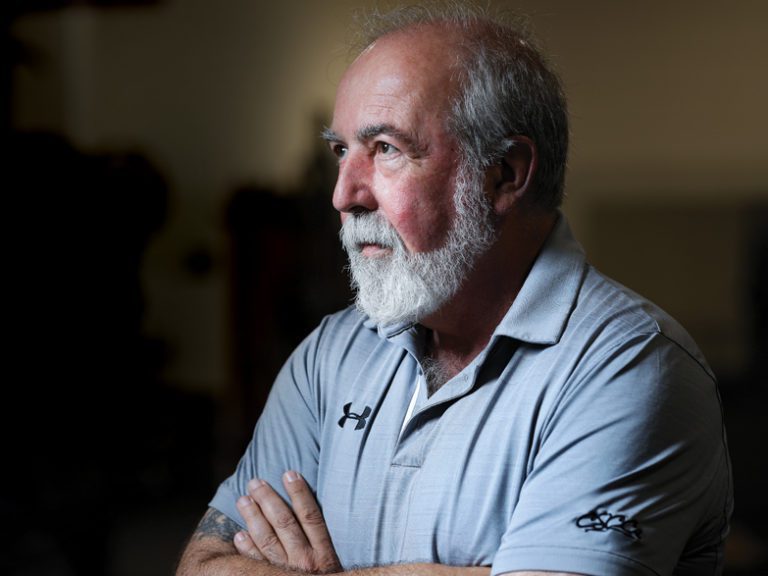

Mike Gentry

When Tony Caterisano joined the health sciences department at Furman in 1984, he was convinced that strength training needed to be an important part of any physical regimen that fosters good health and peak performance.

But he was an outlier in that area. Cardiovascular exercise was considered to be the true way to better health, and a fellow professor in the department, the late and delightfully acerbic Sandor Molnar, never missed a chance to remind him of that.

When Molnar would go for one of his runs, often from the Physical Activities Center to the top of Paris Mountain and back, he would see Caterisano working out in the tiny, underequipped weight room and implore the young professor to join him. It would be good for your heart, Molnar would say, unlike your preoccupation with weightlifting.

“I would say, ‘No, I’m going to lift,’” Caterisano says. “Then he would smile and tell me I would leave a good-looking corpse after I was gone.”

As it turns out, Caterisano was right about strength training. It has long since proven to be every bit as important as cardiovascular exercise for maintaining overall health. It’s no coincidence that over the last few decades, Furman’s PAC has gone from having a couple of little-used weight machines in the basement to a phalanx of new, high-tech equipment at its center.

Caterisano never doubted he was right about the benefits of strength training, but he was determined to prove why through his research. And thanks to a friendship he formed when he was doing graduate work at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he would have a unique way to test what he was learning.

That friend was Mike Gentry, a fellow graduate assistant and powerlifting partner who would go on to become one of college football’s first strength and conditioning coaches at Virginia Tech. The two stayed in close touch, sharing their strength training theories and the research Caterisano was doing at Furman. They would co-author two books –“A Chance to Win” (2005) and “The Ultimate Guide to Physical Training for Football” (2013) –and watch the sport be transformed by the burgeoning size and speed of the players. Virginia Tech, meanwhile, became a college football powerhouse during Gentry’s 29 years at the school, producing ACC championships, All-American players and NFL stars.

“We were developing our own theories, which were sometimes flying in the face of what the books were saying,” says Caterisano, whose theories weren’t purely academic. He has won dozens of weightlifting championships over the years and can bench press 285 pounds at age 69.

‘Strength versus power’

Elijah McKoy ’21 tackles a Wofford player in 2021.

So why have football players become so much bigger, stronger and faster over the past four decades? They’ve always lifted weights and run sprints, but as Caterisano and others have learned, there is a science behind successfully blending speed, size and power.

“When I was growing up, a 300-pound lineman who could run a 40-yard dash in under five seconds was unheard of,” he says. “How does that happen? Don’t tell me it’s steroids. It’s not.”

The answer? Better training, he says.

“It’s knowing the difference between strength and power, and how we develop power differently than we do strength. In the old days, if had a lineman who could squat 600 pounds, I would have wanted to get him to 700 pounds,” says Caterisano.

“But if that lineman can’t play low to the ground and block guys and move his feet fast enough to lead a running back on a sweep, it doesn’t matter how much he can squat.” It became clear that linemen also need to be faster and more agile.

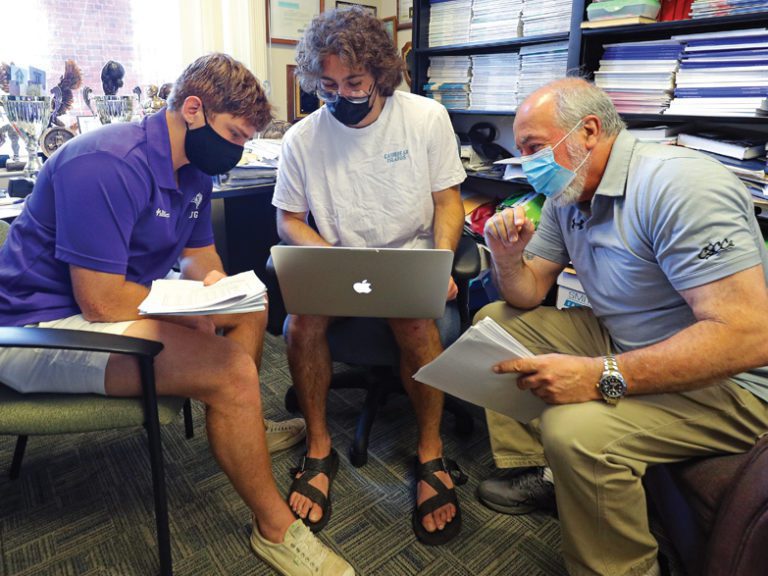

Chase Shaner ’20, Mike Caterisano ’21 and professor Tony Caterisano transfer the Virginia Tech football physical test written data to a spreadsheet to run a statistical analysis.

‘The data – uniquely consistent and copious’

Gentry kept meticulous records during his 29 years at Virginia Tech, compiling reams of data on every football player who came through the program. He routinely tested for size, strength, power, speed and agility, and he updated that information throughout the players’ careers.

When Gentry retired from Virginia Tech in 2016, he made Caterisano an intriguing offer. How would he like to have all the player information Gentry had collected over the years?

“The uniqueness of Mike’s data sets is that they’re so consistent,” Caterisano says. “He was with the same football program for 29 years, testing the players exactly the same way over that time. The more data you have, the more robust the statistical analysis is going to be.”

So Caterisano gladly accepted what may well be the country’s largest and most comprehensive data set measuring the physical improvement of college football players. He enlisted the help of Chase Shaner ’20 and his son, Mike Caterisano ’21, to help organize the information in spreadsheets. It was a labor-intensive, three-year project, especially since some of the early data was handwritten. Then there was the matter of what to do with all that information.

‘A pattern to their success’

Advice posted inside Caterisano’s office

Over 29 years, some Virginia Tech players started, some became All-Americans, some played in the NFL, and some never cracked the starting lineup. Caterisano wondered if it was possible to do a statistical analysis of the successful players and see if there was a pattern to their success.

Since quarterbacks and wide receivers need different skills and training methods than linebackers and linemen, he and the students divided the players into categories and studied them individually. What they discovered would lead to presentations at the American College of Sports Medicine national conventions in 2018 and 2019. Caterisano is preparing the findings for publication.

“You could predict success for skill players (quarterbacks, wide receivers, running backs, defensive backs) when they increased their body mass, benchpress max, back squat max and vertical jump,” Caterisano says.

“Big speed players (tight ends, fullbacks, linebackers, defensive ends) who improved their bench max and 20-yard shuttle time had the most success. For linemen, improvement in the bench press max was the only measure that predicted success.”

Likewise, the players who spent at least two years in the program and never made the starting lineup showed little or no improvement in those critical areas. (“They didn’t get better at the right things.”) Caterisano says he is excited to share his findings with any football coaches who might be interested. He points to the Michael Lewis book “Moneyball,” which chronicled how Major League Baseball’s Oakland Athletics used data and statistical analysis to build a highly competitive team.

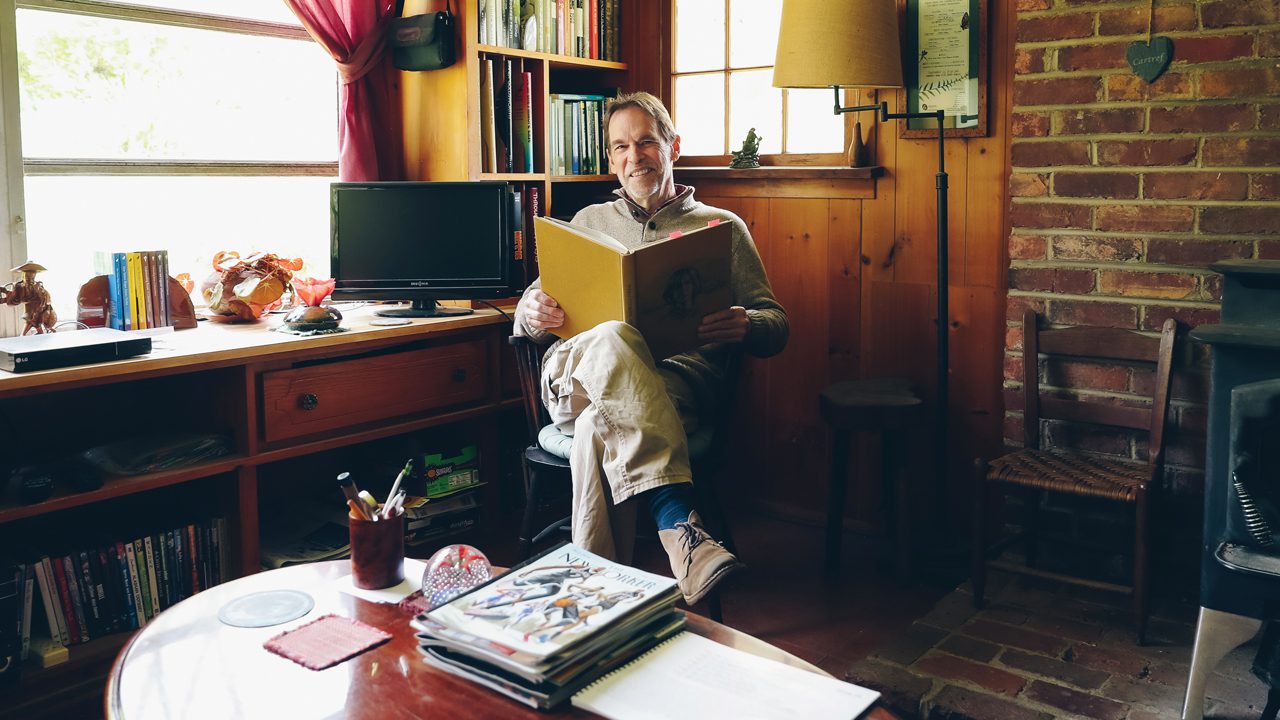

Health sciences professor Tony Caterisano

“I’d like to think a coach could look at our final product and figure out ways to use the data to be more successful, both with their recruiting and their training and conditioning programs,” says Caterisano. “There is some predictive data there.”

Gentry says he is impressed with the work Caterisano and the students did with his data, which he believes verifies that their training theories were correct. And he is particularly thankful he met Caterisano those many years ago at UNC.

“Tony and I had a great partnership, which was a merger of the practical and the scientific,” says Gentry.

“We both had our theories, and I could rely on Tony’s academic background in exercise science to make sense of it all. We made a good team.”